I don’t know about you, but Prairie County having “more than her quota” of crazy people seems kind of ….

My 2nd great-grandfather, Abel Shuford Reinhardt (1847-1935), was the beleaguered sheriff in question, bless his heart.

Ruminations, Research, and Writing

I don’t know about you, but Prairie County having “more than her quota” of crazy people seems kind of ….

My 2nd great-grandfather, Abel Shuford Reinhardt (1847-1935), was the beleaguered sheriff in question, bless his heart.

This is the true story of the greatest interspecies war in recorded history.

The setting is Western Australia, October 1932, so it’s mid-spring Down Under. Spring is migration season when waterfowl and songbirds fly overhead in murmurations and sharp V-formations. Australia also has a migratory bird that does not fly. Emus are large critters. When they migrate, the image that should come to your mind is the wildebeest of Africa, the caribou of the Arctic, or the bison formerly of North America. The 1932 spring migration was the invasion that started the Great Emu Wars.

A decade before, veterans of World War I had been given land in the Western Australia Outback as payment for their service. Western Australia had been threatening to secede for thirty years, and Parliament hoped that the new settlers would turn the tide. When the Depression hit, Parliament encouraged those new farmers to plant more wheat. An abundant wheat crop was growing just in time for migration season.

General Napoleon Bonaparte said, “An army marches on its stomach.” Migrating giant flightless birds discovered that wheat fields make excellent forage. They tore gaps in fences, gorged themselves on wheat, spoiled the crop with their big feet, and invited their allies, the rabbits, to run amok in the fields.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s classic movie The Birds, a character hears that birds have attacked a school and tried to kill children. Skeptical, she says, “Birds have been on this planet since Archaeopteryx, a hundred and forty million years ago. Doesn’t it seem odd that they’d wait all that time to start a… war against humanity?”

A single emu can strip a garden in a couple of hours. A handful of emus can devastate a wheatfield in half a day. Twenty thousand emus were making brisk business of acres and acres of farmland. These birds had declared war on humanity. Humanity had to defend itself.

At first, the farmers fired rifles to scare off the birds, but the sheer number of invaders overwhelmed them. They needed something more. So, they got an audience with the Australian Minister of Defense. They demanded machine guns like those they had used at Gallipoli and ammunition to repel the enemy incursion. And since Western Australia, where the mood favored secession, now asked for federal government help, help was politically expedient.

But the farmers were a dozen years rusty in deploying heavy weaponry. So, the Defense Minister sent highly-trained military personnel in troop transports to fight. Since this mission was as much a military action as a public relations opportunity – surely those grateful Western Australians would stop their silly secessionist talk now! – the Defense Minister also sent a cinematographer to record the whole thing. After all, what could possibly go wrong?

So, on the side of the humans: Major G.P.W. Meredith in command of the 7th Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery, two Lewis machine guns from World War I, 10,000 rounds of ammunition, and two personnel carriers in the form of Model Ts.

On the enemy’s side: an unidentified emu general and his barefoot battalions. Sun Tzu said, “A good commander is unconcerned with fame.” I’m sure this is why we don’t know the name of the humble emu commander.

Because as we will see, the emus had studied Sun Tzu. The Australians had not.

Historian Barbara Tuchman said, “War is the unfolding of miscalculations.” The first miscalculation happened in late October when the humans delayed their participation in the war on account of rain. The sun finally came out on November 2nd; the two sides could play ball. But the birds were no longer clumped in large groups that were easy to find.

Sun Tzu said, “Allow the enemy to think you foolish because their arrogance will cost them the battle.” Being too foolish to come in from the rain, the emus had spread out over miles and miles of farmland while the humans stayed dry. The emus knew exactly what they were doing.

Eventually, someone spotted about 50 emus together. Farmers tried to herd them into an ambush, but the birds scattered. History must assume that the emu commander rallied his troops by reminding them of Sun Tzu’s famous advice: “Be extremely subtle, even formless.” The birds refused to stay in formation, and their tactics confounded the Aussies.

The strategy of the emus was simple. Having read Sun Tzu, they knew that “the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” So, they didn’t fight. They ran away.

Running emus are difficult to target. They’re big birds, sure, but they have tiny heads. Feathers make their bodies seem bigger than they actually are, and they run 30 miles an hour. Salvos from the Lewis guns missed every single one. By the end of the first day, the humans claimed to have killed a dozen birds. Witnesses were skeptical. The cinematographer had caught it all on film. Exhausted from their exertions, the 7th Artillery decided to take a day of rest.

Two days later, on November 4th, Major Meredith received intelligence that a thousand enemy combatants had assembled their forces at a dam. A gathering like this was tailor-made for the Lewis guns. This time, the weapons could surely subdue the enemy and compel a surrender. The humans set up a single Lewis gun and aimed carefully. Staccato fire leaped from the gun, which almost immediately jammed. By the time the soldiers unjammed it, the birds were long gone.

Another human miscalculation was believing that a Model T’s top speed was 45 miles per hour. That top speed assumes paved roads. In the unpaved fields of the Outback, the Model T could barely reach 15 miles per hour, and emus are twice as fast. Only two Model Ts were in the fray. They couldn’t keep up, and the bumpy terrain made firing guns from them impossible.

Napoleon said, “You must not fight too often with one enemy, or you will teach him all your art of war.” By November 6th, the fourth day of the campaign, apoplectic army observers noted that “each pack seems to have its own leader now—a big black-plumed bird which stands fully six feet high and keeps watch while his mates carry out their work of destruction, and warns them of our approach!”

On November 8th, after six days of battle without a confirmed kill, the Australian Parliament called for a cease-fire. It recalled the 7th Artillery, which had spent only a quarter of those 10,000 rounds of ammunition. Major Meredith reported that his troops had killed hundreds of birds, but the newspapers scoffed at that. The cinematographer had evidence. Word on the ground was that maybe 50 birds had been hit, and perhaps a dozen died.

Western Australia was still desperate for relief. Four days after surrendering the battlefield, Parliament relented and sent Major Meredith and his Lewis guns to the Outback again.

Machiavelli said that when the enemy knows your plans, you must change those plans. Instead of one bullet for every two birds, the Aussies brought along half a million rounds this time and prepared for a pitched battle. But Sun Tzu said, “There is no instance of a nation benefitting from prolonged warfare.” Some Australian evidently stumbled across a copy of the Art of War, read that passage, and recommended that the Great Emu War should end for the good of the country. The Australians surrendered the battlefield again less than a month later, on December 10th.

Ultimately, Major Meredith reported that the 7th Artillery had fired 9,860 of its half-million rounds and killed 986 emus – one bird for every ten bullets. His numbers could have been accurate. We know this ratio is possible because a farmer hit an emu with his truck a few days after the detente. The bird’s autopsy revealed nine bullets had been in its body for about two weeks before the truck killed it.

A few months after Australia declared the Great Emu War ended, Western Australia voted overwhelmingly to secede. Secession never happened, though – probably because the people were still too busy trying to fend off guerrilla attacks by emus. Despite pleas from farmers in 1934, 1943, and 1948, the government never sent more help.

As that same character in Hitchcock’s The Birds observed, “The very concept of war with birds is unimaginable. Why, if that happened, we wouldn’t have a chance! How could we possibly hope to fight them?”

Eventually, farmers learned how to build emu-proof fences.

*This post was originally a presentation to the Æsthetic Club on 25 April 2023.

Since early in the months of the pandemic, four of us single, solo-dwelling women have gotten together to flex our culinary muscles and honor the china and silver inherited from various grandmothers. This is our October 2022 dinner:

Soup course: French onion soup with toasted baguette slices topped with creamy Gruyère cheese melted in a broiler for three minutes.

Salad course: Hearts of romaine with homemade croutons, coated with fresh anchovy garlic dressing in a homemade mayonnaise matrix, thinned with lemon juice and a touch of aged white wine vinegar.

Main course: Daube glacé chilled for 24 hours in a demimonde mold, accompanied by homemade mayonnaise, capers, and micro greens, with a squeeze of lemon. Toasted baguette accompanied.

Dessert: Scratch cake embellished with caramel and pecans, then topped with three layers of caramel: homemade caramel sauce, caramel icing, and another layer of caramel sauce. (We call it “the caramel cake.” A two-inch slice instantly induces a sugar coma.)

I try to be a good humanist.

Being a humanist means taking action to make the human condition better. Action doesn’t mean sitting around and thinking about something just hoping for it to get better, which is all that prayer amounts to. (Sorry, prayer warriors, but there have been scientific studies done on this, and prayer doesn’t work.)

Action can be on a small scale – taking a tray of food to a bereaved family, offering to help a friend change bandages after surgery, helping a neighbor with home or car repairs, providing someone a ride to a job interview or watching their kids for a couple of hours, rescuing a starving cat or dog, giving a friend a hug and a compassionate ear, or simply expressing sympathy.

Humanism also means taking action on a large scale. Humanity needs us to protect nature and the threatened habitats of other species, to donate money and volunteer time to ensure that everyone in our communities has a roof over their heads and food on their plates and medical care. For the sake of our own species as well as others, we need to reduce our carbon footprints, advocate for more humane policies and laws, and vote out lawmakers who make life harder, not easier, for marginalized people.

Being a humanist means being kind to other people and to the world around us. Religious people can do this, too, and often do.

I sincerely wish they’d keep their wishful thinking to themselves, though. Offering nothing beyond vague “thoughts and prayers” sounds insulting to me. The person saying it has noticed there’s a situation, but absolutely refuses to do anything about it – and tells us so. That’s the opposite of humanism.

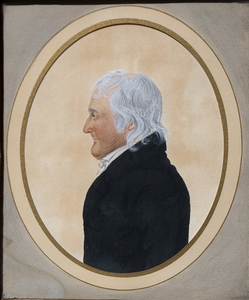

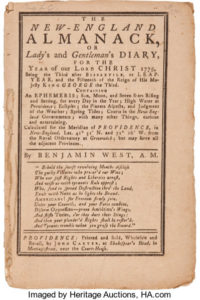

One of my favorite ancestors is Dr. Benjamin West (1730-1813) of Providence, Rhode Island.1Not to be confused by the famous English/American painter Benjamin West (1738-1820), who was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1791. Their circles sometimes overlapped, and many genealogies conflate the two. That’s his marble bust at the top of the page. Brown University has it.2 It was recently restored.

The 1822 obituary of my 5th great-grandmother, Mary “Polly” Smith West Pearce, referred to her father as “the eminent Dr. Benjamin West” of Providence. I had not known who her parents were before I found that obituary. What followed were several days of frantic discovery on my part, each one better than the last. The man was phenomenal, and I don’t understand why every generation after him hasn’t continued to hold him up as the pinnacle of the Enlightenment. (Actually, there are many males named “Benjamin West” in the Robinson branch of our family, so someone clearly remembered him. My line from him has been daughter-intensive for the last four generations, so I suppose there’s a reason for it to be missing.)

Benjamin West was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American equivalent of England’s Royal Society. Although he was a merchant for about 25 years, he earned great respect as a teacher and a university professor. He taught at Philadelphia’s eminent Protestant Episcopal Academy and at the College of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (now Brown University) in Providence. Brown University owns his portrait.3Dr. Benjamin West (1730-1813), Professor of Mathematics, Astronomy, and Natural Philosophy, 1786-1799. Artist unknown; Watercolor silhouette, 3½” x 7½” from the portrait collection of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. Gift of the family of Dr. West. Portrait 156, Brown Historical Property No. 1853, located in the John Hay library 122. From the Brown University website: “The painter of this miniature portrait is unknown … It was a family portrait during Benjamin West’s lifetime and after his death in 1813 it was prized by his descendants for generations until it was ultimately donated to Brown.” Portrait Collection, Office of the Curator, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, website (https://library.brown.edu/cds/portraits/display.php?idno=86). His life and work are fabulous examples of the Enlightenment in North America.

Benjamin West was born in March 1730 in Rehoboth, in Massachusetts Bay, one of the New England Colonies. His father was a farmer. When Benjamin was a young child, the family moved to Bristol. At the time, both Massachusetts and Rhode Island claimed jurisdiction over Bristol.

Benjamin was an autodidact. After a mere three months of formal education and without the means to buy books, Benjamin borrowed every book he could. His most significant benefactor during his childhood was a fiery Congregationalist minister in Bristol named John Burt.4Rev. John Burt died while fleeing the bombardment of Bristol by the British on 7 October 1775, at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Benjamin West had known Rev. Burt well for thirty years at that point – from his childhood to his marriage to Elizabeth Smith. We can assume that the bombardment of his hometown and the death of his friend and mentor made the war personal for Benjamin West. See Wilfred Harold Monro, The History of Bristol, Rhode Island, Providence, Rhode Island: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1880, 208, digital image, The Internet Archive (www.archive.org : accessed 6 Mar 2022); and “A Revolution is Brewing,” The Rhode Island Slave History Medallion Project, Linden Place newsletter, Bristol, Rhode Island: Linden Place (www.lindenplace.org : accessed 6 March 2022). Around the time of his 1753 marriage to Elizabeth Smith when he was 23, he moved to Providence, Rhode Island (population ~3,3005United States Bureau of the Census. A century of population growth from the first census of the United States to the twelfth, 1790-1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909. p. 162. The Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/centuryofpopulat00unit/page/162/mode/2up). He lived most of the rest of his life in Providence.

By 1758, Benjamin found backers to help him open a dry goods store. A couple of years later, he opened the first bookstore ever to grace the commercial avenues of Providence, now paying for the books he wanted by selling them to other people. He published almanacs for Providence, Bristol, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, to supplement his income for nearly 40 years. His work in plotting and recording the transit of Venus across the sun in 1769 was recognized in 1770 when the College of Rhode Island, then newly established on College Hill in Providence, awarded him an Honorary Doctorate of Letters.

During the Revolutionary War, he manufactured clothing for soldiers in the Continental Army while publishing his almanac and pursuing his scientific studies. The Royal Society of London published his paper on the transit of Venus and Mercury. In 1781, Benjamin West became a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 1786 began to teach mathematics and astronomy at the College of Rhode Island. In later years he added natural philosophy to the curriculum.

His friends were early backers of the College of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, which later became Brown University. Providence was a small town in those days, so he naturally came into regular contact with the progenitors of the school: Stephen Hopkins (a signer of the Declaration of Independence), the famous four Brown brothers (Nicholas, Joseph, John, and Moses), Judge Daniel Jenckes, and others. He loved mathematics and astronomy and conferred with some genuinely great minds of his day. He tutored students privately throughout his life.

Benjamin West was a member of an active abolitionist group in Providence. This position pitted Benjamin against his friend John Brown, who actively engaged in the slave trade. Except for John, the Brown brothers’ thoughts on slavery shifted after a disastrous series of events on their slave ship Sally. Of 196 people purchased on its two-year voyage to Africa, only 87 survived to be sold as slaves in Antigua. The inhumanity of the Sally debacle especially shattered Moses Brown. He manumitted the people he had enslaved and became one of the most outspoken abolitionists of his time.

Purple prose and flowery metaphors abound in the contemporary biographical accounts, some written around the time of his death. They all reach one conclusion: Benjamin West was a genius who contributed considerably to science and mathematics. He was indeed a product of the Age of Enlightenment.

An event in 1766 opened some gilded doors for him. A comet appeared in the constellation of Taurus on the evening of April 9. Being an excellent self-taught astronomer, Benjamin took careful measurements. He wrote a letter to a Boston astronomer named John Winthrop,6The Harvard President was a direct descendant of the John Winthrop whose 1630 fleet began the Great Migration. The earlier Winthrop was the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the persecutor of Anne Marbury Hutchinson. who was at Cambridge College (now known as Harvard University). He had never met or corresponded with Winthrop but was so excited about his observation he simply had to share it – and shared it with one of the foremost astronomers in North America.

Providence, April 10, 1766

Dear Sir:

For the improvement of science, I now acquaint you, that the last evening, I saw in the West, a comet, which I judged to be about the middle of the sign of Taurus; with about 7 degrees North latitude. It set half after 8 o’clock by my watch, and its amplitude was about 29 or 30 degrees. Nothing, Sir, could have induced me to this freedom of writing to you, but the love I have for the sciences; and I flatter myself that you will, on that account, the more readily overlook it.

I am, Sir, yours,

Benjamin West

This flowery language essentially says, “Sorry to bother you, but wow! I saw a comet last night!” He and Winthrop became great friends and continued to write to each other. For the rest of their lives, they would share observations about the night sky.

In 1716, building on the work of Johannes Kepler a century before, Edmund Halley figured out how to apply the theory of parallax to determine the distances between astronomical bodies. With both Mercury and Venus predicted to pass between Earth and the sun in 1769, astronomers worldwide were anxious to test the theory. Since this was the first opportunity to view the transits of both inner planets since Halley’s theory was published, everyone in the field of astronomy was excited. Captain Cook would observe the 1769 transit of Venus from Tahiti on his ill-fated circumnavigation. At the time of the last transit of Venus in 1761, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, who had just finished their survey of the boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland, had traveled to the Cape of Good Hope to observe it. These men used astronomy as an essential tool in their lives – navigating the oceans and surveying the land required precise measurements, and measurements started with the stars.

There was no telescope in Providence in 1769. Benjamin West, Stephen Hopkins, Joseph Brown, and Moses Brown were determined to see the phenomenon, though, so they managed to import a telescope from England at the incredible expense of 500 pounds. The men set up on the outskirts of Providence and watched the celestial event. Transit Street in Providence is named after the spot where they viewed the transit on June 3, 1769. There are photos of the telescope on the Brown University website – the school still has it and displays it.

As was his habit, Benjamin West made careful measurements of the transit.7See a list of Brown University’s observations of the transits of the planets at the Ladd Observatory. He published a tract (and dedicated it to his friend Stephen Hopkins) about the event.8See a copy of the 27-page tract on the Brown University website, complete with diagrams.

In July 1770, he and other astronomers observed the new;y-discovered Lexell’s Comet, which passed closer to earth than any known comet before or since. His observations contributed to a theory about the tails of comets. Because of his astronomy observations and publications, Benjamin West, a man with only three months of formal education, was awarded an honorary Master of Arts from Harvard on July 18, 1770. Here’s the text of the notification letter from his friend John Winthrop:

Cambridge, July 19, 1770

Sir —

I have the pleasure to acquaint you that the government of this college were pleased, yesterday, to confer upon you the Honorary degree of Master of Arts; upon which I sincerely congratulate you. I acknowledge the receipt of your favour, and shall be glad to compare any observations of the satellites.

Yours,

John Winthrop

Benjamin West primarily worked as a merchant during the 1760s and 1770s. When the Revolutionary War finally arrived, commerce dried up. He went to work manufacturing clothing for the American troops, but he continued his studies and correspondence with the other great minds and kept publishing his almanacs. In 1772, Dartmouth College awarded him an honorary degree for his work in astronomy. Then, in 1781, he was elected in the first class of honorees to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Some of his correspondence survives in the Academy’s archives. Two articles by Benjamin West appear in the Academy’s inaugural journal. First was the three-page article, “An Account of the Observations Made in Providence, in the State of Rhode-Island, of the Eclipse of the Sun, Which Happened the 23d Day of April, 1781.” He and Joseph Brown observed the eclipse together, and they would continue to share observations of the sky their entire lives.

Mathematics seems to have been Benjamin’s first love. In 1773 he wrote to a friend in Boston of a theorem he had developed to extract “the roots of odd powers” that was probably his most significant contribution to the field of mathematics. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences published a copy of his letter in its first journal. This article was entitled “On the Extraction of Roots.” It caused a sensation on both sides of the Atlantic. He created theorems in quadratic equations to extract the third, fifth, and seventh roots of numbers. Some skeptics claimed his theorems were no different from those already in use; others praised their clarity and simplicity.

He didn’t stop at math and astronomical observations, though. One surviving biography explains a physics problem he cogitated upon for more than two years in conjunction with John Winthrop and a Mr. Oliver. It had to do with the properties of air in a copper tube that was then placed into an otherwise airless container. The qualities of invisible gases – basically, the scientific understanding of the very concept of the physical nature and properties of “air” – were in their infancy. Benjamin West speculated about the attractive and repulsive nature of the tiny particles that made up the matter of air and how they would behave under different conditions. (We now call these particles “molecules.”) Gravity, matter, magnetism, and ultimately the behavior of the tails of comets played into his understanding of the question.

Benjamin West’s mind was at the peak of its illuminating brilliance as the world around him heaved. His most important discoveries and writings happened as the American Revolution was about to explode. By the end of the Revolution, he had returned to academic pursuits. He tutored students in math and astronomy. In 1786, the College of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations offered him a full professorship.

For some reason, he did not begin teaching at the college for a couple of years. Leaving his wife and family in Providence, Benjamin West moved to Philadelphia temporarily to teach at the illustrious Protestant Episcopal Academy. While there, he solidified relationships with the influential minds of that city, including Benjamin Franklin and David Rittenhouse. He assumed his post at Brown in 1788.

Brown University awarded Dr. West his first non-honorary degree, his Doctor of Laws, in 1792. He taught mathematics and astronomy there from 1788 until 1799. After leaving the university, he opened a navigation school and taught seafaring men astronomy. He clearly felt called to teach other people the wonders of the universe. I found an advertisement in the Providence Gazette published 29 March 1783 in which he and other influential men of Providence were reconstituting the local library and organizing its books.

Almanacs are annual publications that include helpful information on many practical subjects. People in farming, fishing, sailing, and other trades relied on their weather forecasts, high and low tides tables, ferry times, stagecoach times, and planting dates. Astronomical events like the phases of the moon and eclipses could be found within their pages, as could folklore, proverbs, poetry, essays, recipes, religious calendars, and more. The Franklin brothers (James and his apprentice Benjamin) were famous for their almanacs. Some of the most significant competitors to Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac were the New England almanacs published by Benjamin West.

One of Franklin’s chief rivals was Benjamin West, who published his almanacs in Boston … West usually used the pseudonym “Isaac Bickerstaff,” a name famously used by Jonathan Swift several years earlier. “Abraham Weatherwise” was also a pseudonym [used by West], and likely used by a number of different almanac printers, and he “ushered in the healthiest and most interesting period of almanac making.”9“Eleven Early American Almanacs, 1733-1795, Including Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard Improved, 1755,” Bauman’s Rare Books, citing Sagendorph, 116. This auction offering, for $15,000, includes two (and possibly five) of Benjamin West’s almanacs.

Benjamin West’s first almanac was published for 1763 on Providence’s first printing press by William Goddard. It was published continuously for 118 years – continued under the pseudonym “Isaac Bickerstaff” and with various titles until 1881. “From 1763 to 1781, Benjamin West was the author, with the exception of the year 1769 when “Abraham Weatherwise” took his place. From 1781 to 1881 “Isaac Bickerstaff” was given as the author, except in 1833, when the name of R. T. Paine appeared on the title page.”10Howard M. Chapin, “Checklist of Rhode Island Almanacs 1643-1850,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 25:19-54 (April 1915), p. 23.

John Carter published the almanacs from 1770-1814.11Howard M. Chapin, “Checklist of Rhode Island Almanacs 1643-1850,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 25:19-54 (April 1915), p. 23. John Carter was the father-in-law of Nicholas Brown, Jr., after whom Brown University was named. Nicholas’s uncle Joseph had secured the telescope to observe the transits of Mercury and Venus and observed them with Benjamin West in 1769.12Howard M. Chapin, “Checklist of Rhode Island Almanacs 1643-1850,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 25:19-54 (April 1915), p. 24. The two men engaged in a conflict over publication rights in 1766. Carter continued publishing (and complaining when others published the same almanac, apparently with West’s consent). Around 1781 the men resolved their conflict. Their relationship continued for the rest of Benajmin West’s life.13Howard M. Chapin, “Checklist of Rhode Island Almanacs 1643-1850,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 25:19-54 (April 1915), pp. 25-26.

Benjamin West did not limit his almanacs to dry data and noncontroversial proverbs. Almanacs during the Revolution and the period leading up to it often included political essays and even propaganda. Since nearly every literate household owned and used almanacs regularly, the political leanings of the publishers and almanac writers influenced the sentiments of the people reading the almanacs. When George III ascended the throne in 1762, Benjamin West’s almanac praised him.14Allan R. Raymond, “To Reach Men’s Minds: Almanacs and the American Revolution, 1760-1777, The New England Quarterly, September 1978, 51:370-395, 372 http://www.jstor.org/stable/364614. However, the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 changed everything, and, as it turned out, Benjamin West did not hesitate to share his passionate political opinions. He was one of the “notable patriots” publishing popular almanacs throughout this period.15 Marion Barber Stowell, “Revolutionary Almanac-Makers: Trumpeters of Sedition.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 73, no. 1 (1979): 41–61, 42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24302752.

Benjamin West, mathematician and Brown University professor, was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society. From 1763 through 1781 he published almanacs in Providence, Rhode Island. That West calculated the almanacs does not necessarily mean that he wrote the contents. The printers often hired a calculator, whose name, if it were prestigious, was given to the almanac. Frequently the printer himself furnished the additional text. For 1766 in “A Short View of the present State of the American Colonies, from Canada to the utmost Verge of His Majesty’s Dominions,” the author clearly states that his description of the general despair in English America is to propagandize: “such being the deplorable Situation of this Country, once renown’d for Freedom, it is hoped a Review thereof will excite such a universal Spirit of Patriotism in every Inhabitant, that our Liberty and Property may be yet rescued from the Jaws of Destruction.”16ibid, p. 45. The article’s author notes that “The West almanac for 1766 was printed by Sarah Goddard and her son, William. On 21 Sept. 1765 William Goddard published his sensational Constitutional Courant, a patriotic polemic for the Whig cause.” That being said, Benjamin West’s own strongly Whig sentiments are not lost to history.

His 1767 almanac contained an essay protesting strongly against the Stamp Act and is credited with being one of six critically important almanac-based essays on the topic.17Allan R. Raymond, “To Reach Men’s Minds: Almanacs and the American Revolution, 1760-1777, The New England Quarterly, September 1978, 51:370-395, 374 http://www.jstor.org/stable/364614.

His 1775 almanac contained “A brief view of the present controversy between Great Britain and America, with some observations thereon.” It filled three pages of the 25-page almanac. Benjamin West’s friend and mentor, Rev. John Burt, would die on October 7, 1775, during the British bombardment of Bristol.

Rev. John Burt was the fifth pastor of the Congregational Church in Bristol, R.I. He assumed his duties on 13 May 1741. He died at the age of 50, on 7 October 1775,18Find a Grave memorial # 13165832 for John Burt, at the Congregational Churchyard cemetery in Bristol, R.I. (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13165832). as the British bombarded the town in the first year of the Revolution.19During the Revolutionary War, the British Royal Navy bombarded Bristol twice. On October 7, 1775, a group of ships led by Captain Wallace and HMS Rose sailed into town and demanded provisions. When refused, Wallace shelled the town, causing much damage. The attack was stopped when Lieutenant-Governor William Bradford rowed out to Rose to negotiate a cease-fire. Bristol and the neighboring town of Warren, RI, suffered a second attack by the British on 25 May 1778, when 500 British and Hessian troops marched through the main street (now called Hope Street (RI Route 114)) and burned 30 barracks and houses, taking some prisoners to Newport.

Rev. Burt was born in Boston and educated at Harvard. After the French and Indian War of the 1750s-1760s, Burt was adamantly anti-Catholic and anti-French.19John F. Quinn, “From Dangerous Threat to “Illustrious Ally : Changing Perceptions of Catholics in Eighteenth Century Newport,” Rhode Island History, 2017, 75:56,60, accessed 6 Mar 2022. At the time of the 1790 census, only 3,211 lived in Bristol county, a little less than half of which lived in the town of Bristol.

It takes little imagination to believe that Rev. Burt’s death during the shelling of Bristol by the British inspired Benjamin West to take action on the American side, even if he had not been inclined that way before. However, Benjamin West’s published almanacs make clear that his sentiments lay strongly with the American cause long before the first official shots were fired at Lexington and Concord.

Since I discovered him as Mary Smith West’s father, the rest of Benjamin’s family has been a brick wall for me. “Brick walls” in genealogy research refer to those ancestors whose origins and relations are shrouded in seemingly impenetrable mystery. Of course, I may have gotten so wrapped up in researching the man that I haven’t put enough energy into the rest of the family!

Most secondary sources list Benjamin’s father as a farmer named John and his wife as Elizabeth Smith. A couple of these sources say Ben’s grandfather was an immigrant to America, but his name is not given. Several sources claim he had eight children and was survived by three of them, but as of March 2022, I have found names for only four or five: Elizabeth, Nancy (Anne?), Benjamin, Mary “Polly” Smith, and Joseph.20Rhode Island Census, 1774, p. 53, Record for Benjamin West in Providence, Rhode Island. Ancestry, website (www. ancestry.com : accessed 6 Mar 2022). In his household, there were two white males over the age of 16, one white male under the age of 16, two white females over 16, and three white females under 16. Assuming he and his wife are two of the people over 16, this report allows for two sons and four daughters in the household. Two others may have died young, been living elsewhere, or not yet born. Where his wife’s maiden surname is mentioned, it is given as Smith. His birthplace is given as Rehoboth, Massachusetts, or Bristol, Rhode Island. In 1730 Bristol was claimed by Massachusetts as part of the original Plymouth colony. It became part of Rhode Island in 1746, when the border between Rhode Island and Plymouth colonies was finally settled. Bristol was where King Philip’s War had started in 1675, and served as the primary base of operations for Metacomet, or King Philip. If Benjamin’s family was in the area at the time, they would have endured the first (and worst) of the wars between Native Americans and European colonists. The town was started in 1680, after the war.

Many online trees confuse and conflate Benjamin West the astronomer with another Benjamin West born in Rhode Island around 1730. The other Benjamin West (c. 1730-1782) was the son of William West (1681-aft 1742) of Kingstown, Rhode Island. William was the son of Susannah Soule (c. 1642-c. 1684) and Francis West (c1632 in England – 1696 in Kingstown). Susannah was the daughter of Mayflower passenger George Soule (c1601 in Holland – c. 1680 in Duxbury, Plymouth Colony). The descendant of George Soule is said to have been born in North Kingstown or Newport, Rhode Island, around 1730. He is said to have lived in Farmington, Connecticut, and died in Rensselaer, New York in 1782. The “Silver Books” of the Mayflower Society list the 1753 marriage record of Benjamin West and Elizabeth Smith as belonging to George Soule’s descendant, not to the astronomer. Since the astronomer was from Bristol, and the Soule descendant was from Kingstown, it seems more likely that the attribution of the marriage record to the Soule descendant is incorrect.

There is a marriage record for Benjamin West and “Mrs. Elizabeth Smith” in Bristol, County, Rhode Island, on 7 June 1753.21James N. Arnold, Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636-1850, Vol. 6: Bristol County, pp. 50, and citing Bristol Marriage Record Book 1:125. Providence, Rhode Island: Narragansett Publishing Company, 1891-1912. Rev. John Burt performed the marriage ceremony. Based on the title she was given in the marriage record, she may have been married to a man named Smith prior to marrying Benjamin West. However, no other records in Bristol show a man named Smith marrying a woman named Elizabeth in the 10 years prior to this. It is possible that she married elsewhere. It is also possible that “Mrs.” was simply an abbreviation for “mistress” and did not denote her previous marital status.

In 1767, Benjamin West was a commissioner for the insolvent estate of Joseph Smith, deceased, of North Providence (Pawtucket). He valued the estate and filed papers confirming the portion that should be allowed to Joseph Smith’s widow, Marcy or Mercy Smith.22 “Probate files, early to 1885 (Pawtucket, R.I.),” Pawtucket (Rhode Island). Court of Probate. Probate files, 1, 5-85, Estate of Joseph Smith (1768), images 363-373 of 1199, FHL Film 2364533. FamilySearch (www.familysearch.org : accessed 6 March 2022) Joseph may have been a brother or another relative of Benjamin’s wife.

Elizabeth Smith West may have been a daughter of Anne Arnold, the widow of Benjamin Smith who married Stephen Hopkins in 1755. Hopkins was a signer of the Declaration and a colonial governor of Rhode Island, among his many other accomplishments, and was known to be a close friend of Benjamin West.

Benjamin’s wife Elizabeth died in 1810 in Providence. When Benjamin died in 1813, the probate court appointed two administrators: his daughter Elizabeth, who apparently never married, and his son-in-law Gabriel Allen, who was married to Benjamin’s daughter Nancy. Nancy was a nickname for Anne, so her name appears as both in records. It appears that Joseph, Elizabeth, and my 5th great-grandmother, Mary “Polly” Smith West Pearce, were the children who survived him.

In the first Decennial Census of the United States in 1790, Benjamin West lived next door to his son-in-law, Oliver Pearce. Oliver was married to Benjamin’s daughter Mary Smith West, who was called Polly. They were my 5th great-grandparents. In 1800, the Pearces had moved, but Gabriel Allen, who married Ben’s daughter Nancy (or Anne), lived next door. In Ben’s home were four white adults: a man and a woman over 45 and a man and a woman between the ages of 26-44. The younger couple may have been one of their children and a spouse or possibly two adult unmarried children.

Oliver Pearce and Polly West moved to Fayetteville, North Carolina, sometime between 1793 and 1807. By 1800, Oliver’s brother Nathan was already living in Fayetteville, North Carolina with another adult male and two enslaved people.

A man named Benjamin West died in Providence in 1801 and may have been Benjamin and Elizabeth’s son. One of Benjamin’s sons also may have been named Joseph. Joseph West, a Revolutionary War veteran from Rhode Island, married Violetta Howard of Baltimore County, Maryland, and died there in 1840. I’ve gone a bit back and forth as to whether he’s the right Joseph Smith, and have found nothing definitive to connect him to the astronomer despite the repeated insistence of quite a few unsourced online trees.

More information is out there, but not accessible to me online. Brown University’s John Hay Library has in its special collections letters from Benjamin and Joseph West to Dr. Solomon Drowne23in the Drowne Family Papers (MS Drowne). The Rhode Island Historical Society has documents in its special collections relating to Benjamin West’s mercantile business and a narrative of his 1769 observations of the transits.24Benjamin West Papers, MSS 794. There are references to him in the papers of Moses Brown at the same repository.25MSS 313. Letters from Benjamin West to one of his granddaughters, Cecilia Pearce Newby (a daughter of my 5th great-grandmother), are in the special collections at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with the papers of her husband, Larkin Newby.26Larkin Newby Papers, 1796-1884. Collection Number: 03247.

American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Website (amacad.org : accessed 6 March 2022).

Arnold, James N. Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636-1850, Vol. 6: Bristol County, p. 50, citing Bristol Marriage Record Book 1:125. Providence, Rhode Island: Narragansett Publishing Company, 1891-1912. (FamilySearch.org : accessed 6 March 2022).

Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of the Harvard Press, 1967, 50th Anniversary Edition, 2017.

“Biography of Benjamin West, L.L.D. A.A.S.: Professor of Mathematicks, Astronomy and Natural Philosophy, in Rhode Island College – and Fellow of the Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, &c.”, The Rhode Island Literary Repository, Vol I, No. 7 (October 1814): 137-160 (337-360). Google Books (books.google.com : accessed 6 March 2022).

Bliss, Leonard. The History of Rehoboth, Bristol County, Massachusetts: Comprising a history of the present towns of Rehoboth, Seekonk, and Pawtucket, from their settlement to the present time; together with sketches of Attleborough, Cumberland, and a part of Swansey and Barrington, to the time that they were severally separated from the original town. (Boston: Otis, Broaders, and Company, 1836). The Internet Archive (archive.org : accessed 6 March 2022).

Brown University. Portrait Collection, Office of the University Curator, Providence, Rhode Island. Website (https://library.brown.edu : accessed 6 March 2022).

Find A Grave. Website, database with images (findagrave.com : accessed 6 March 2022).

Hall, Louise. “Family Records: Newby Bible”, New England Historical and Genealogical Register 122 (Apr 1968): 125-128, 125. American Ancestors (americanancestors.org : accessed 6 March 2022).

Mitchell, Martha. “Benjamin West”, Encyclopedia Brunoniana (1993).

Newmann’s Ltd. Website (newmansltd.com : accessed 6 March 2022)

Pease, John Chauncey, and John Milton Niles. A Gazetteer of the States of Connecticut and Rhode-Island, (Hartford: William S. Marsh, 1819), 331-333. Biographical entry for Dr. Benjamin West. (Google Books : accessed 6 March 2022.)

The Providence Gazette, various issues, 1763-1802.

Quinn, John F. “From Dangerous Threat to “Illustrious Ally : Changing Perceptions of Catholics in Eighteenth Century Newport,” Rhode Island History Journal, 75:56, 60 (2017). Rhode Island Historical Society (www.rihs.org : accessed 5 Mar 2022.

Raymond, Allan R. “To Reach Men’s Minds: Almanacs and the American Revolution, 1760-1777.” The New England Quarterly 51, no. 3 (1978): 370–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/364614.

“A Revolution is Brewing,” The Rhode Island Slave History Medallion Project, Linden Place newsletter, Bristol, Rhode Island: Linden Place (lindenplace.org : accessed 6 March 2022).

Rhode Island Historical Society Library. Benjamin West Papers. 121 Hope Street, Providence, RI 02906.

Spencer, Mark G. Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of the American Enlightenment, Entry for Benjamin West (1730-1813). London: Bloomsbury (2015). pp. 1096-1097.

Stowell, Marion Barber. “Revolutionary Almanac-Makers: Trumpeters of Sedition.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 73, no. 1 (1979): 41–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24302752.

United States Bureau of the Census. A century of population growth from the first census of the United States to the twelfth, 1790-1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909. p. 162. The Internet Archive (archive.org : Accessed 6 March 2022).

Wikipedia. (wikipedia.org : accessed 6 March 2022).

+++

An earlier version of this post originally appeared on Aramink.com.

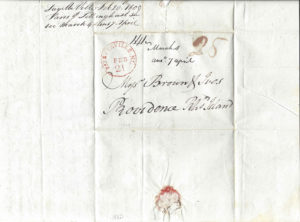

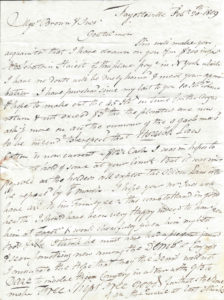

A few years ago, I had the extraordinary good fortune to come into possession of a letter written by my 5th great grandfather, Paris Jenckes Tillinghast (1757-1822), to “Messers Brown & Ives.” The letter was written 20 February 1809, postmarked the next day, received 4 March 1809 in Providence, and answered on 7 April 1809.

This letter was so full of family connections that I nearly hyperventilated when I saw it on eBay. I lost the auction but persuaded the winner to rehome the letter. Fortunately, he was also interested in family history and understood my excitement.

Fayetteville Febry 20th 1809

Messrs Brown & Ives

Gentlemen

This will make you acquainted that I have drawn on you for $200 in favr Mr Sebastian Staiert of this place payl in N York which I have no doubt will be duly honord & meet with your approbation. I have purchased since my last to you 10 Hnd Tobacco & hope to make out the 45 Hnd in time for the Augus return & not exceed $3 Hn. The planters are now asking more on acct the rumour of the (??a garlemesd??) to be intendd to be repeald that Horrible Law. Cotton is now current at $12½ Cash. I was in hopes to [ge]t hold of some at your limits. But it was improbable as the holders all expect the Odious Law is to be repeald by 4th March. I hope your Mr Ives will have arrd to his Family eer this comes to Hand in good health. I should have been very Happy indeed to have seen him at Fayetl & would chearfully given him my best bed & table. I think he must have had a pleasant jaunt & seen something new among the Demots at Congress. I anticipate the Hope that they the Demos will not Dare to involve their Country in a War with GB to make Free Ships Free Goods for that’s the Bone of all the Quarrel at last I think. Please to inform me your opinion respecting the price of cotton with you & in Boston I shall have a Debt due in Boston next month & wish to know If cotton will do the honors and I have pickd up some few Bales for this purpose. I will do all I can to hand you your pay as fast as I can possible get hold of anything But would (empower?) for your Interest. O Pearce Daughter Eliza intends to take a Husband on Thursday Evening next a Dr Robinson of this town to be Happy man. A good Demo he suits OP well. He is Nephew to the Senator from Vermont now in Senate US. I wish them all the happiness they can desire &tc. I can’t help telling you Mrs Huske had a fine Boy 31st Janry She & child finely. My best wishes for your & family Happiness

& Remain yours Respectfully

Paris J Tillinghast

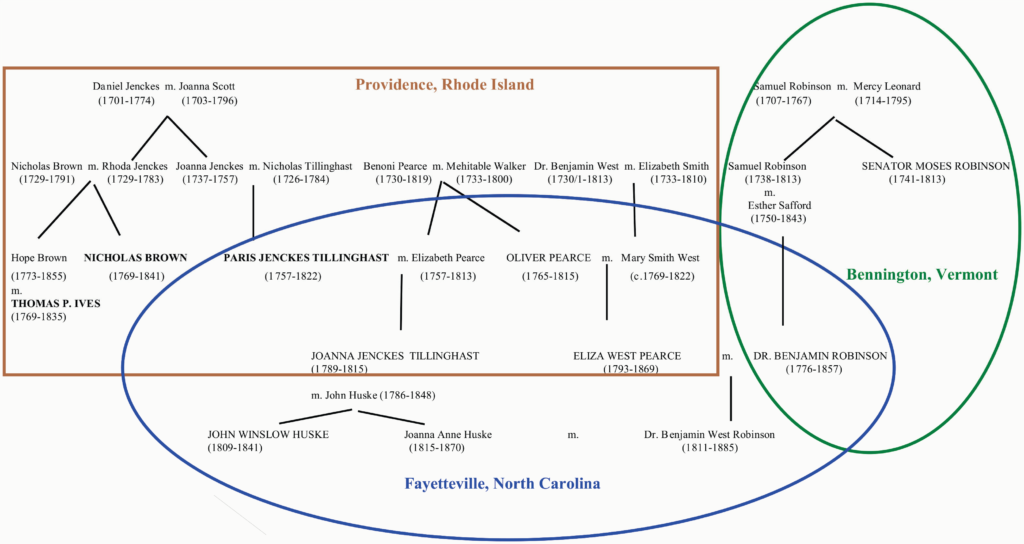

Nicholas Brown and his brother-in-law, Thomas Poynton Ives, owned an international trading company called Brown & Ives. It was the successor to a series of companies owned by various members of the Brown family for three generations. Thomas Ives was apprenticed to a previous iteration of the Browns’ company, became a partner, and ultimately became family when he married Nicholas Brown’s only sister, Hope.

Nicholas and Hope inherited the shipping business of their father and three uncles, the famous four Brown brothers of Providence, Rhode Island. Their father and uncles had focused on conventional goods, but a significant portion of their fortune came from the transatlantic slave trade. The Brown family – especially Nicholas – donated a lot of money to Rhode Island College, so the school renamed itself Brown University in the family’s honor. (You may have heard about Brown University’s examination of its part in the slave trade a few years ago.) Hope Hall at Brown University is named for Hope Brown Ives, the sister and wife of the men addressed in this letter. Nicholas and Hope were the only surviving children of Nicholas Brown, Sr., and his wife, Rhoda Jenckes.

Nicholas and Hope’s maternal ancestors also made a significant mark in early New England. Their maternal grandfather, Daniel Jenckes, was a prominent judge, politician, and landowner. The first patent in North America was granted to Daniel’s great-grandfather. His grandfather founded Pawtucket. His paternal uncle, Joseph Jenckes, was a prominent Rhode Island politician and colonial governor of Rhode Island. Governor Jenckes also married a Brown: Nicholas’s great-aunt Martha.

The author of this letter to Nicholas Brown and Thomas Ives was my 5th great-grandfather, Paris Jenckes Tillinghast. His mother, Joanna, was Rhoda Jenckes Brown’s sister. He was also a grandson of Judge Daniel Jenckes. Therefore, Paris was writing to his first cousins.

Paris’s letter first addresses business. In 1804, Paris had emigrated to North Carolina from Rhode Island with his wife’s brother, Oliver Pearce. (Oliver was married to Mary Smith West, a daughter of the astronomer and polymath Dr. Benjamin West of Providence.) The “Horrible Law” and “Odious Law” that Paris is so upset about in the letter is likely the controversial Embargo Act of 1807, which made international trade illegal. The Act intended to stop privateer attacks on American merchant marines and prevent Americans from being impressed by the British to fight against France, but it nearly devastated the American economy. Since Brown & Ives, like other Brown family entities before them, were engaged in international trade, the Embargo Act nearly crippled them. As Paris anticipated, Congress repealed the Embargo Act two weeks later and replaced it with the somewhat less onerous Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which prohibited trade only with England and France. (The Non-Intercourse Act wasn’t any more popular than the Embargo Act.) The War of 1812 was looming.

I do not know the extent of the Tillinghast and Pearce involvement in Brown & Ives. This letter indicates some shared interest, whether by association, contract, or perhaps even employment. Given the amount of international trade from the Carolina backcountry at the time, Paris Tillinghast and Oliver Pearce may have moved to North Carolina to further the business interests of Brown & Ives and then been hindered by the Embargo Act. For generations after this letter, they were merchants, among other things. For at least three generations before Paris, the Jenckes and Tillinghast men had been ship captains and traders to the West Indies.

The Browns had supplied Dr. Benjamin West Robinson with the telescope he used to observe the transits of Venus and Mercury in 1769, so there is a known connection of the Browns to the Pearce family through Dr. West’s daughter. And, of course, all of these families had roots in Providence, which was a relatively small city at the time. In 1769, Providence’s population was about 3,300 people; by the date of this letter, fewer than 10,000 people lived there.

The Browns had supplied Dr. Benjamin West Robinson with the telescope he used to observe the transits of Venus and Mercury in 1769, so there is a known connection of the Browns to the Pearce family through Dr. West’s daughter. And, of course, all of these families had roots in Providence, which was a relatively small city at the time. In 1769, Providence’s population was about 3,300 people; by the date of this letter, fewer than 10,000 people lived there.

That’s not all the family news, though. In the letter, Paris tells Nicholas that his wife’s niece, Eliza West Pearce, had met Dr. Benjamin Robinson – the nephew of Senator Moses Robinson of Vermont – and that they would soon be married. Paris also reported that his daughter, Joanna Jenckes Tillinghast Huske, had given birth to a healthy son. This son was John Winslow Huske (1809-1841), the eldest brother of Joanna Anne Huske. Joanna Anne Huske grew up to marry her second cousin, Dr. Benjamin West Robinson. They are my 3rd great-grandparents.

The diagram puts everyone in a tree and in the places where they were (and where they were from). The names of the people mentioned in the letter are ALLCAPS, and the sender and recipients are bold. I also transcribed the letter. Please let me know if anyone can make out any of the writing that I couldn’t read.

Hope Brown was named for her paternal grandmother, Hope Power. The Brown, Power, West, Pearce, Jenckes, and Tillinghast families entangled over generations in Providence and continued entangling with each other and with Huskes, Starks, and Robinsons once they arrived in North Carolina.

At the beginning of the letter, Paris refers to Sebastian Staiert, to whom Paris had advanced some of Nicholas’s money. Sebastian’s daughter Ann married John Jennings, a great-uncle of my 2nd great-grandmother, Laura Pemberton. Two generations after this letter, Laura would marry Oliver Pearce Robinson and bring him to Arkansas to run the plantation she had inherited. That plantation – we now just call it a farm – has been in our family since the 1850s.

We’ve been cleaning out Fletch and Shirley’s house and looking hard for the missing Smith family bible from the 1800s without any luck. I’m so glad that I scanned the genealogy pages years ago – it makes me sick that we can’t find the book now.

That Bible has always been a mystery to me. At one point, it apparently belonged to Averilla Hollis Frank, who never had any children. All of her adult life, my son’s 4th great-grandmother – Skip & Matt’s 3rd great-grandmother, Frances A. “Fanny” Gash Smith – lived with Averilla, Averilla’s mother, or another of the Hollis sisters. Fanny is buried with Averilla’s mother, Martha Hollis, in Brooksville, Kentucky. We don’t know how Fanny and the Hollises were related, but Fanny’s son Henry [Barnard or Barnet] Smith ended up with Averilla’s Bible. That’s the one that is now missing.

Fanny’s husband, O.F. Smith, is also a mystery. I have found only two records for him besides Averilla’s Bible: the record of his marriage to Fanny in Kentucky, and his death, which was recorded in the 1880 census mortality schedule in Polk County, Iowa – over 600 miles from Fanny and their son Henry in Kentucky. The census reported that he died at the county’s poor farm. One record says he was born in Ohio; the other says he was born in Pennsylvania. For a man named Smith, that’s not much to go on.

This afternoon, on a high shelf at the Smith home, I found a worn album of tintypes, daguerrotypes, and old studio photos from the 1850s through the 1890s. There was a note from one of the childless Smith relatives inside. Shortly before her death at a great old age in the mid-1990s, this relative had written to Fletcher that she didn’t know who the people in the album were but wanted him – her only living relative – to have it. One of those photos is identified as Averilla Hollis Frank. Others are identified, but the names aren’t familiar to me. More have no identifying information beyond the studio’s name, and sometimes its location (always in Ohio), printed on the cards.

Next, I reached for the worn, leather-bound book shelved beside that album. Its spine was illegible, but the name “John Barr” was inked thickly into the edge of the pages opposite the spine. I opened it. Scrawled inside the front cover was a poem of sorts, or possibly a dedication: “John Barr his hand and this 18th day of March 1838 / Steal not this book my honest friend for fear the gallows may be your end. Oliver P. Gash March the 18th 1838.”

Oliver was one of the Gashes who lived in the Ohio/Kentucky area where Fanny lived, but I had not made a firm connection between them. My heart started beating fast. “Matt, look! Here’s a dedication to someone named Gash!”

I flipped the page. It was a bible! It isn’t one of the big ones we normally find from that time, but an ordinary-looking book about the size of a fat mass-market paperback. I flipped through, but no interior genealogy pages appeared. Then I flipped to the back cover.

Names. Dates. All of them Gashes.

“Oliver P. Gash was born July the [ ] 1817” – meaning he was 20 when the front matter was written. “Martha Elizabeth Gash was born February the 9, 1827.” “Fanney Ann Gilbert Gash was born November 14th, 1829.”

“FANNY! It’s FANNY!” I exclaimed.

By now, Matt was standing right next to me. “You just got chill bumps,” he observed. Chill bumps? I was shaking. Ecstatic!

Names of Gashes I have not been able to connect to Fanny appeared in order by date of birth, in different inks, in pencil, and in different handwriting. I turned the page. They had to be her siblings. Right? I had found them, but they were not firmly connected to one another like this. For a few years now, my working hypothesis has been that they were siblings, but I didn’t have anything to support that other than they lived in the same area at the same time and were close in age.

Below the Gash entries, I could barely make out, “Henry Bernet Smith, born October 5, 1851.” Fanny’s son! Then, “Barnard Preston Gash was born June the 23, 1786.” “Isabel Gash was born August the 2, 18__” “Bernard P. Gash died March 1837.” “Isabel Gash died December 12, 1874.”

And then, “Fanny G. Smith died July 28, 1886.”

Oliver was only 12 years older than Fanny, so he couldn’t be her father. Barnard Preston Gash died the year the youngest Gash child listed in this Bible was born. Could he have been Fanny’s father and Isabel, her mother? Isabel appears in the census as head of household in 1840, 1850, and 1860, with children but never a husband. I had wondered if she might be Fanny’s mother.

But who was John Barr? One of the recorded births is Martha Jane Barr, born January 3, 1837. Now I wonder about the family relationship between John Barr, Martha Barr, and all these Gashes!

Flipping back to the front of the bible, I found an obituary for Martha A. Shetler, the wife of George Shetler, Sr. She was the mother of four children and died in Marshalltown, Iowa – near where Fanny’s husband, O.F. Smith, died. The obituary said she was born in Ohio and married in Pennsylvania.

And later, when I picked up the book to photograph it for this post, I saw that a copy of a genealogy page from Averilla Hollis’s Bible – the very one that originally identified Fanny Gash and her husband O.F. Smith to me – is pasted into the front of this bible, too, carefully folded to the right size to have been undetected when my shaking fingers first started looking for names in this little book.

Today’s treasure trove of the little bible and the photo album may crack the Smith/Gash ancestry mystery. Now I need time to puzzle it out – although a few more hints and records would help!

UPDATE: We found Averilla’s Bible!

Those of you who have worried incessantly about my immortal soul can relax now.

When I die, I will become one with the Internets.

Just stick me in one of the tubes.

There are many who will applaud my conversion. They have been worrying about my soul for a while. We all need something to feed our souls. They will be glad I’ve found nourishment.

Maybe one of my high-tech-inclined friends will work on a method of fabricating special soul cable from human ashes. Then people who want to be one with the internet can donate their earthly remains to make soul cable, and we will all share the same soul in an interconnected series of Internet tubes. The manufacturers might even be able to get their raw material for free with the promise that those Left Behind can still communicate with those who have moved on to a different planar existence in the internet. They could call it Soylent Green Fiber.

The Church of Google has compiled a list of Nine Proofs of the divinity of Google. This is better than Martin Luther’s 95 Theses because it’s written in a language we can understand.

I am ashamed, but nevertheless, I shall copy these proofs from the website, in the spirit of evangelical proselytizing:

» PROOF #1

Google is the closest thing to an Omniscient (all-knowing) entity in existence, which can be scientifically verified. She indexes over 9.5 billion WebPages, which is more than any other search engine on the web today. Not only is Google the closest known entity to being Omniscient, but She also sorts through this vast amount of knowledge using Her patented PageRank technology, organizing said data and making it easily accessible to us mere mortals.

» PROOF #2

Google is everywhere at once (Omnipresent). Google is virtually everywhere on earth at the same time. Billions of indexed WebPages hosted from every corner of the earth. With the proliferation of Wi-Fi networks, one will eventually be able to access Google from anywhere on earth, truly making Her an omnipresent entity.

» PROOF #3

Google answers prayers. One can pray to Google by doing a search for whatever question or problem is plaguing them. As an example, you can quickly find information on alternative cancer treatments, ways to improve your health, new and innovative medical discoveries and generally anything that resembles a typical prayer. Ask Google and She will show you the way, but showing you is all She can do, for you must help yourself from that point on.

» PROOF #4

Google is potentially immortal. She cannot be considered a physical being such as ourselves. Her Algorithms are spread out across many servers; if any of which were taken down or damaged, another would undoubtedly take its place. Google can theoretically last forever.

» PROOF #5

Google is infinite. The Internet can theoretically grow forever, and Google will forever index its infinite growth.

» PROOF #6

Google remembers all. Google caches WebPages regularly and stores them on its massive servers. In fact, by uploading your thoughts and opinions to the internet, you will forever live on in Google’s cache, even after you die, in a sort of “Google Afterlife”.

» PROOF #7

Google can “do no evil” (Omnibenevolent). Part of Google’s corporate philosophy is the belief that a company can make money without being evil. (I’m not so sure about this particular proof. Google has failed in this regard, but it may be doing it only to test our faith. You know, like the Republican White Yahweh and the dinosaurs.)

» PROOF #8

According to Google Trends , the term “Google” is searched for more than the terms “God”, “Jesus”, “Allah”, “Buddha”, “Christianity”, “Islam”, “Buddhism” and “Judaism” combined.

God is thought to be an entity to which we mortals can turn when in a time of need. Google clearly fulfills this to a much larger degree than traditional “gods”, as shown in the image below.

» PROOF #9

Evidence of Google’s existence is abundant.There is more evidence for the existence of Google than any other God worshiped today. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. If seeing is believing, then surf over to www.google.com and experience for yourself Google’s awesome power. No faith required.

Thirty years ago this week, the Berlin Wall fell. It encircled only part of the city, dividing it between East and West and serving as a metaphor for the contrasting ideologies of Eastern and Western Europe at the time.

Borders mark where one authority begins and another ends. We mark our borders with laws and signposts and walls. Sometimes, we can’t really see where the border is, but we know generally that over here is one place, and over there is another place. In 1889, 25-year-old journalist Rudyard Kipling was assigned to cover conflicts near the Khyber Pass, one of the few ways through the Hindu Kush and across the border between Afghanistan and what was then British India. Kipling described the pass as “a sword cut through the mountains” because the weather and terrain of the pass kill people. The mountains themselves were this border’s wall. The Pass lies on one of the main routes of the Silk Road that stretches across borders from Shanghai in the East to Spain in the West. In the shadow of that 10-foot-wide pass, Kipling wrote, “East is East, and West is West, and never the two shall meet.”

When British India split, the East remained India and Hindu, and the West became Pakistan and Muslim. The two shall never meet—except at the precisely choreographed “Beating Retreat” ceremony that has been performed at the Wagah-Attari border crossing for the last sixty years.

Picture this: a pair of ornate iron gates blocks passage on the road, a white line painted on the pavement between them (just like the floor of the bedroom you shared with your sister when you were eight); the black uniforms of the Pakistani Rangers trimmed in white, and on their heads, a giant black cockscomb rises at least two feet high. On the other side of those gates, Indian Border Security Forces wear khaki. Not to be outdone by the Pakistanis, they also wear giant cockscombs on their heads—in bright orange-red.

It’s the end of the day and time to lower the flags and go home. Drums beat a frantic tempo. On both sides, a master of ceremonies leads a call and response with grandstands packed with hundreds of spectators who wave flags and yell with nationalist fervor. This is a border pep rally. Machine gun-toting, sword-brandishing guards flex their muscles, grimace, and point thumbs down at their cross-border rivals. They march with giant steps and high kicks straight out of Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks. The guards on the opposite side of the gates are doing the exact same thing—same steps, same thumbs down, same silly walks. The ceremony ends with the lowering of flags and an exaggerated handshake between an Indian guard and his Pakistani counterpart.

Here’s a taste of the Beating Retreat border ritual:

And here’s a longer version. It’s quite a sight.

The Wagah-Attari border has been called the Berlin Wall of Asia. The Berlin Wall was that other place where East was East and West was West, even though “West” only meant a portion of a Western city surrounded on all four sides by East. The Wagah-Attari border may be the most uniquely ritualized one in the world, but the Berlin Wall is the standard by which all other borders are measured.

In the wake of World War II, France, the U.K., the U.S., and the Soviets each were to occupy a portion of Germany and its capital, even though Berlin lay 100 miles inside the Soviet zone of occupation. But in 1948, the Soviets tried to evict the other three allies from Berlin by imposing a land and river blockade. They cut power and stopped distributing food in the western-occupied sections of the city. The West responded with the Berlin Airlift, and the conflict between East and West ramped up.

Borders are arbitrary. They are a line drawn in sand, a mark on a map, a gate across a road. The idea is to keep things separated, to keep the bad guys out and the good guys safe.

A long time ago, on a continent far, far away, Mongol hordes regularly invaded their southern neighbors. The Southerners built a series of walls that were eventually joined into one because they were so tired of the constant invasions by those bad hombres. North is north, and south is south, and never the two shall meet in peace, right? I know this because I was once married to a man who refused to vacation north of the Mason-Dixon line, which, he firmly maintained, cut somewhere between Nashville and Louisville.

Chinese schoolchildren are taught that the Great Wall of China can be seen from space. When one of their astronauts admitted that he couldn’t see the wall despite trying hard with extra-sharp astronaut-caliber eyesight, there was some discussion of rewriting Chinese textbooks. But walls, it seems, are too important to let facts get in the way. Although China’s Great Wall can’t be seen from space, its air pollution can. Some things just don’t respect borders.

People challenge borders. A matched pair of graves in the Netherlands sit in two cemeteries. The wife was Catholic, and her husband was Protestant, so they could not be buried in the same cemetery. They were laid to rest against the wall that divides the Catholic cemetery from the Protestant one. A stone hand reaches out from the top of each of their tombstones and clasps the hand from the other, defying the wall between them. Walls are made to be breached, and borders are made to be crossed.

Kipling’s “Ballad of East and West” starts with the western theft of an eastern horse. The theft was only possible because borders are porous. Under Soviet occupation, it turned out that many inhabitants of the Eastern Bloc preferred living in the West. Berlin’s border was very porous. Defectors found their way to Berlin and from there to the West through one of the 81 crossing points in the city.

After 15 years of defections, the Berlin Wall was built almost overnight in August 1961. Guards now simply shot people trying to cross from East to West. The Brandenburg Gate entered the collective consciousness as a symbol of freedom denied. The wall cut workers off from their jobs, prevented friends from seeing each other, and separated families. East was East and communist and totalitarian, and West was West and capitalist and democratic, and the two could not possibly coexist.

The Berlin Wall was not the first such border. In 1953, as East and West and North and South struggled for dominance in the Cold War, a line was drawn between the Koreas. Despite its name, the Korean Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ, is probably the most heavily militarized border in the world. Like at Checkpoint Charlie, people in the DMZ’s no-man’s-land risk being shot on sight.

In the 1970s, South Korea discovered four tunnels beneath the DMZ and accused the North of planning an invasion. The North hotly denied it, claiming the tunnels were coal mines. They had even blackened the walls of one tunnel to prove it. Oddly enough, the DMZ welcomes 1.2 million tourists every year, and yes, the tunnels are on the itinerary. Tourists can enter a conference room in a building that sits in both countries just to say they’ve been to the North. And there’s an observatory in the DMZ.

Unlike the Great Wall of China, the dividing line between the Koreas can be seen from space, at least at night when South Korea is as brightly lit as any other first-world country and North Korea is pitch-dark, not unlike a coal mine.

The Berlin Wall attracted tourists, too. In the summer of 1983, I went to Europe with a Eurail pass, a backpack, and a loose cadre of companions. When we arrived in Salzburg it was raining too hard for sightseeing, so a couple of the women in our group boarded a train for Berlin. They somehow got a visa to enter East Berlin. They saw a typical modern city when they got off the train in West Berlin. When they crossed to the other side of the wall, though, dull, brutalist, concrete block architecture greeted them. There were no neon signs or billboards. The people seemed as gray as the buildings. A week later, in Amsterdam, my friend Michelle was still stunned as she described the stark difference between East and West.

East is East, West is West, North is North, and South is South, but people don’t define themselves by directions on a compass. Borders give a false impression that something significant lies on the other side. Borders sometimes may be more of an idea than a reality.

Hadestown is a relatively new musical on Broadway. It re-tells the myth of Orpheus trying to rescue his beloved Eurydice from the Underworld. Hades has put Eurydice and other unfortunates to work building a wall. Hades asks them, “Why do we build the wall?” “To keep us free,” they respond. “How does the wall keep us free?” “It keeps out the enemy.” “Who is the enemy?” “The enemy is Poverty.” Hades reminds the builders that the people on the other side of the wall want what the Underworld has: freedom–and a wall. Of course, no one is free to leave the underworld once they arrive.

The inequity of the Berlin Wall was immediately apparent to the West. Two American presidents, 25 years apart, stood before the wall and condemned it. John F. Kennedy gave his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in 1963. In 1987, Ronald Reagan stood at the Brandenburg Gate and spoke directly to the Eastern leaders, saying, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

Two years after Reagan’s speech, in the summer of 1989, reform and revolution spread through the Soviet Union and the satellite states of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Hungary. East Germans fled their country in droves. On November 4, 1989, half a million angry protesters filled the streets of East Berlin near the wall. To try to keep the population happy, on November 9th the East German government announced it would allow people to pass through checkpoints if their documents were in order. A journalist asked when the new rules would take effect. The government spokesperson didn’t know, so he said, “Immediately.”

But no one expected that it would just end, especially as it did—within hours. The news was broadcast at 8:00 that evening throughout Berlin. People began amassing at the wall demanding passage. At 10:45, lacking instructions and knowing that the announcement had been made, guards began allowing people through. East Germans swarmed the gates and were greeted jubilantly by West Berliners with flowers and champagne. The West claimed credit for the fall of the wall and the raising of the Iron Curtain that followed.

Saturday, on the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, some citizens of Berlin sent a gift to the people of the United States. They inscribed a 2.7-ton slab of the Berlin Wall with a letter addressed to President Trump, which closed with: “We would like to give you one of the last pieces of the failed Berlin Wall to commemorate the United States’ dedication to building a world without walls.”

The White House rejected the gift. Apparently, our president doesn’t want a wall after all.

This post was originally a paper presented to the Æsthetic Club on 12 November 2019.

Robert Harrison Poynter (1844-1902) was a Methodist minister who rode a circuit in southeastern Arkansas in the latter part of the 19th century, preaching and otherwise interacting with local people. He had served in the Confederate forces in Arkansas during the Civil War. He kept a diary from January 1896 until just a couple of weeks before his death of pneumonia in 1902. The first section of the diary is an account of his life.

I unearthed a typescript of the diary a few days ago when I sorted through a box of family history ephemera and treasures. The box in which I found it had been in storage for at least four years. The items in the box came from lots of different sources. They included 100 years of photographs, miscellaneous documents dating from the 1930’s to the 2010’s, 40-year-old letters and 25 years of printed emails related to family history research, a scrapbook that had belonged to my grandmother as a child, concert ticket stubs spanning 1975-2004, brochures from vacations from the 1950’s through 2004, my great-grandfather’s legal files (he died in 1967), mementos from the first Clinton-Gore presidential campaign, and so many other various and sundry items they defy exhaustive description.

I found a reference to Rev. Poynter’s diary online. As of 1995, the actual diary belonged to L.D. Poynter, Jr., of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. I assume that the diary’s owner is a descendant of Rev. Poynter. Rev. Poynter’s obituary was printed in the Minutes of the Methodist Episcopal Church South for 1902 and is available online.

Typed copies of newspaper articles, handwritten family group sheets, and handwritten notes about the diary are appended to it.

As best I can tell, Rev. Poynter was not a relative of mine and did not interact with anyone in my extended family. Creation of an index to the people and places mentioned in the diary would greatly assist other researchers of southeastern Arkansas history and genealogy. I don’t think I’m going to take on that project any time soon, though!

I wish I knew how this typescript came into my possession. I would gladly give credit to the person who spent great effort and considerable time creating it. If you know about this diary or the creator of the typescript, please contact me.