The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette gave significant print space today to state senator Jason Rapert to let him deny that he ever called for Judge Chris Piazza’s impeachment. (It seems the paper printed the story, and then refused to issue a correction despite Rapert’s demands, so they allowed him to submit a “guest column.”)

You may recall that Judge Piazza declared the ban against same sex marriages unconstitutional, which raised Rapert’s Neanderthal hackles. Rapert’s screed focused on the will of the people as opposed to the foundational laws of our country – at least, the will of 753,770 people who voted a decade ago against letting any pair of consenting adults marry.

Oh, and God, God, God. Because God. Or, at least, Senator Rapert’s version of a god.

From Rapert’s essay:

I believe the current culture war on marriage between one man and one woman is a symptom of the degradation of the fundamental principle that is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution–that our government is based upon “We the People.”

We, the people of this country and of each state, do indeed elect those who make our laws. Occasionally, in the case of a referendum (the ban on same sex marriage was a referendum back in 2004), we the people actually vote on whether something should be a law. But we don’t all vote – not even when we’re eligible.

Judge Piazza decided that 750,000 individual citizens of our great state, representing 75 percent of the electorate at the time, were wrong, and their sense of morality and beliefs no longer mean anything in Arkansas. In reality, he rendered a judgment essentially saying that the will of an overwhelming majority of the people in our state means nothing and their votes do not count.

But did the majority of Arkansans, actually reject same sex marriage? Did we, the Arkansas people, actually speak with a strong voice about this matter?

Arkansas has a population of around 3 million people, 3/4 of which are over 18. According to the United States Election Project, 54% of the population eligible to vote in Arkansas made it to the polls in November 2004, when the legislature’s referendum was on the ballot. The total turnout was 1,070,573 – about a third of the actual population of the state. Nearly 2 million Arkansans were eligible to vote.

About 1/4 of the population of the state was sufficiently incensed over the notion that equality might happen that they beat a path to the polls in that election to vote against equal marriage rights for their LGBT neighbors, friends, and family members. Not a majority of the population. Not even a majority of the population over 18 or a majority of eligible voters. Just a majority of people who voted on that issue decided to maintain an unequal status quo.

It gets better:

Judge Piazza and activist judges like him … are saying they no longer respect the values, traditions and mores of the majority of the population in our nation and that they singularly have the right to impose the will of a small vocal group upon the rest of our state and the nation.

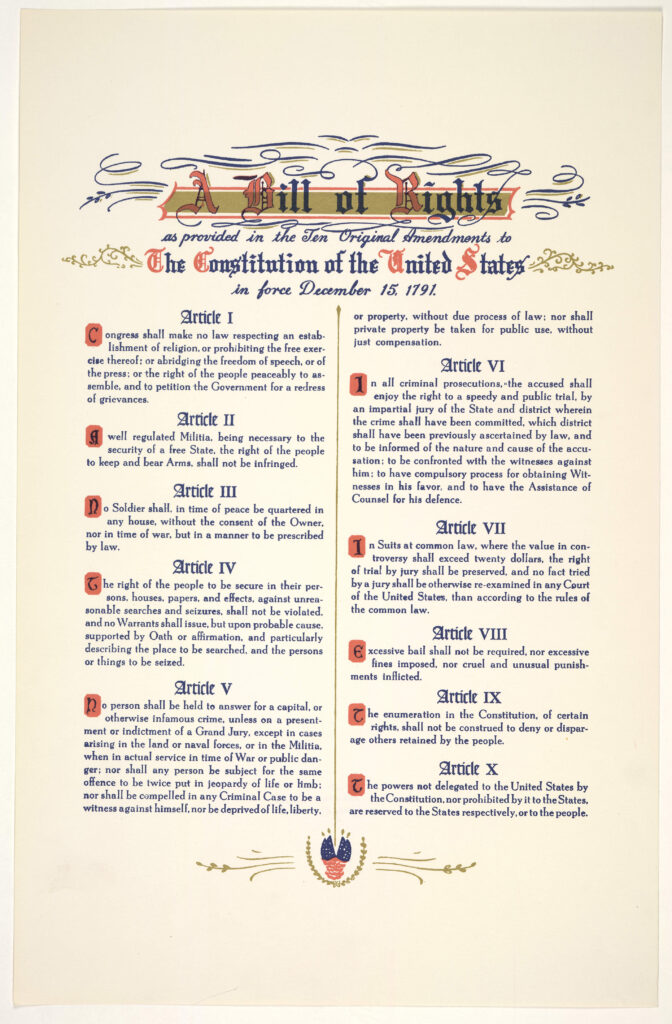

More than anything, this quote from his essay underscores Sen. Rapert’s lack of understanding of both the concept of separation of powers and the role of the judicial branch of government. It also tells me that a man charged with the responsibility of making laws does not understand that there is this foundational document called the United States Constitution that gives him – and the judges who overrule him – that authority. The U.S. Constitution and the Arkansas Constitution define the roles of each branch of government and explains how checks and balances work. Where state and federal laws conflict, federal law trumps.

Changing that foundational document takes much more than the proverbial “act of congress,” and ever since Marbury v. Madison was decided in 1803, the judicial branch was confirmed as that branch of government endowed with the responsibility of interpreting how laws should be applied. Therefore, judges like Chris Piazza are doing their jobs – not engaging in activism – when they interpret laws withing a constitutional framework. We don’t have to like their decisions. If we don’t like their decisions enough, we can appeal them to a higher court, until the buck stops with the US Supreme Court. Ultimately, the language of the United States Constitution applies.

Jason Rapert and his ilk don’t like the decision. Rather than wait for the appellate process to weave its constitutional magic, they scream like banshees at the idea that other human beings – human beings who are a tiny bit different from them – will get treated like actual full citizens of this state and country.

Rapert felt the need to make a number of points about how awful it is for the nasty homos to call themselves a family:

As for the context of the debate raging in our nation and now in Arkansas over same-sex marriage, there are a few things that must be said.

First, honoring the sanctity of marriage between one man and one woman whether out of a sense of morality or based upon one’s religious faith does not mean that a person hates homosexuals.

With this quote, we see what the problem is. Jason Rapert really wants to live in a Christian theocracy. Of course, not a theocracy defined by, say, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Quakers, or Evangelical Lutherans. Nope – he wants a Southern Baptist or fundamentalist evangelical theocracy. In other words, if someone else’s religious beliefs don’t mesh with Rapert’s, then they obviously shouldn’t have the right to hold those beliefs.

And he doesn’t hate homosexuals – he just doesn’t think they are really “people” and that they shouldn’t have the same rights to the pursuit of happiness as “real” people. Of course he doesn’t hate them. How can you hate someone that isn’t really a person? It would be like hating a doll or a tree or a puppy. It’s like accusing an atheist of hating God. It’s not possible to hate something that doesn’t exist.

Rapert’s claim of a “sanctity” of marriage is the big giveaway. Marriage is a contract between two people. It isn’t a sacred state; it’s a legal one. Sure, the couple can have their marriage blessed, and because that blessing is important to many people the state generously allows religious leaders to file their credentials with the state and empowers them to confirm the existence of the marriage in a religious ceremony. The bottom line, though, is that the state has the final say over whether someone is married or not and over who can sign the marriage license. The legal documents have to be in order. The mere act of blessing the couple’s union is not sufficient to marry them. And by virtue of their elected or appointed office, nonreligious people also have the power to marry people.

Furthermore, to dissolve a marriage is akin to dissolving any other legally binding contract. What the state has joined together, the state must split asunder.

Rapert goes a step further in his “I don’t hate” insistence:

I do not personally hate anyone who has chosen a homosexual lifestyle and I believe they should be able to live their lives in peace like anyone else.

Really? Then why is he so gung-ho to deny them the basic and fundamental right to form a family with the partner of their choice? Why does he want to deny them the rights that heterosexual spouses have when it comes to matters like health care decisions? Why does he want to deprive them of inheritance and property rights like dower and curtesy? Why does he want to deprive them of the parental rights to children they have raised together? Why does he want to deny them the tax status granted to legally married partners? Why does he want to deny them the ability to obtain insurance as a family? Why does he want to deny them retirement benefits a spouse would normally get automatically? Why does he want to refuse them the privilege of not testifying against each other in court? Clearly, he does not want them to be able to have the same rights, privileges, and protections “like anyone else.”

Oh, there’s a reason for that, according to Senator Brother Rapert. “[M]arriage is integral to the concept of family, and research shows that children are given the best opportunity for well-rounded social development when they are raised in homes with a mother and father.”

Sure, children do better when there are more adults with a hand in child rearing. The gender of the parent-figure doesn’t matter, nor does the gender orientation of that parental figure. The fact that there is a stable home with the same adults in the household matters.

Not just one, but several factors tend to forecast a happy, successful child. Stability of the family is a paramount predictor of a child’s success. Based on all the research gathered to date, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) has concluded that “[l]ike all children, most children with LGBT parents will have both good and bad times. They are not more likely than children of heterosexual parents to develop emotional or behavioral problems.”

Canada agrees. In 2006, the Canadian Psychological Association reiterated its 2003 position on the issue:

CPA continues to assert its 2003 position that the psychological literature into the psychosocial adjustment and functioning of children fails to demonstrate any significant differences between children raised within families with heterosexual parents and those raised within families with gay and lesbian parents. CPA further asserts that children stand to benefit from the well-being that results when their parents’ relationship is recognized and supported by society’s institutions.

Therefore, if this is all about the children, validating the union of same-sex parents will go much farther to stabilize families than telling the kids that they don’t have a “real” family at all.

Senator Rapert calls a marriage between one man and one woman “natural” marriage. Once again, he displays his ignorance on a sleeve.

Marriage is whatever the law deems it to be. Let’s look at how marriage laws used to be:

Out of all that, he picks only one style of marriage to be “natural.” Blinders make the world a lot less expansive, don’t they?

Mildred Loving might find his comments ludicrously funny. She would have noted the irony that completely escaped Justice Clarence Thomas in his dissent in the DOMA and Prop 8 cases that were decided a year ago: but for a US Supreme Court finding that equal protection was violated by the anti-miscegenation statutes on the books of many of the states, his own marriage and family would not be recognized as valid.

Senator Rapert claims he’s not prejudiced.

Fourth, the tactics of intimidation toward those who object to same-sex marriage, including comparisons to racism, are unfair, unwarranted and shameful. When I was invited to join over 100 African American pastors on the steps of the Arkansas Capitol just a few days ago as they took a public stand for marriage between one man and one woman, that argument began to fall completely apart.

He actually wants us to believe that his embarrassingly solitary white face in that crowd of black pastors was because they invited him, not the other way around.

The comparison to racism is unfair? Why? Because giving equal rights to people born with a different skin color is different somehow from giving equal rights to people born with a different gender orientation?

Let’s imagine for a moment that in 1859, there was a vote in some slave state (just for giggles, let’s pick Arkansas) to preserve the status quo and make it illegal for the government to free the slaves. Heck, let’s take it one step further and suggest that in this vote, any black people who weren’t slaves would automatically become slaves unless they left the state before the end of the year. The state was determined to maintain an unequal status quo.

Impossible, you think?

Nope. That totally happened.

Rapert then claims that the bad press he’s gotten is because people don’t like his “stance on marriage and also as the sponsor of the Arkansas Heartbeat Protection Act.” He is absolutely right. His ideas are completely repulsive to those of us who value our individual liberties, autonomy over our own bodies, and the freedom to make very personal choices for ourselves. He claims that these are the acts of “liberal extremists.”

If only “liberal extremists” are in favor of same sex marriage, then we have generations of “liberal extremists” to look forward to. Liberal policies are the hallmark of progress, while conservative policies tend to be just the opposite. Senator Rapert, like many Tea Party Republicans, goes beyond maintaining a status quo, though. His policies are regressive and authoritarian. Passing statutes for no good reason other that wanting to deny equal rights to a segment of society they find distasteful is a reprehensible way to govern. He does not deserve the office he holds, nor do his like-minded comrades in office. Their policies are fascist.

It’s all about Senator Rapert’s religion, when it comes right down to it:

The America I was taught to honor and respect would never force Christians to do anything that violated the tenets of their beliefs. We have freedom of religion in this nation, not freedom from religion altogether.

No one is forcing anyone else to get gay-married. They aren’t forcing them to go gay-grocery shopping or to gay-teach students. No hate-filled Christian has to have gay sex or even decorate with glitter or rainbows. They don’t have to hire gay interior decorators, get their air trimmed by gay stylists, or wear clothes designed by gay designers. They also don’t have to benefit from the use of computers conceived by gay Alan Turing or read books and plays by gay Oscar Wilde or Gore Vidal. They can switch the channel when Ellen comes on. They can boycott Wachowski films like the Matrix trilogy, Cloud Atlas, and V for Vendetta. They don’t have to patronize LGBT businesses and art any more than LGBT people have to patronize those who proudly proclaim their prejudices and hate.

What they cannot do, though, is refuse service to any LGBT person on account of their hate. As it did upon the demise of Jim Crow laws, the Heart of Atlanta case will provide the precedent to prevent discrimination by businesses through the application of the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution.

Oh, and that dig about freedom from religion? Yes, that’s actually a thing. It’s also the law. If we don’t have freedom from religion, we can’t possibly have freedom of religion. Otherwise, courts would be in the business of establishing religion, and telling us which tenets we have to observe and which we don’t. And the First Amendment to the US Constitution says that can’t happen.

But Senator Rapert feels victimized:

It is very interesting that Christians are targeted so heavily with the venom of the homosexual lobby because most all other major faith traditions do not embrace homosexual marriage either, including Islam.

I would suggest to Senator Rapert that perhaps because they invoke their religion as the reason someone else can’t do something, they seek to establish their religion as the law of this country. And like I mentioned above, they don’t want to establish the denominations that are tolerant of other people’s private behaviors. They want to establish an authoritarian, restrictive, invasive religion. That is entirely, absolutely, completely, and decidedly unacceptable. If the Muslims were the ones doing the screaming and quoting the Qur’an as the reason we shouldn’t allow certain people equal rights, Senator Rapert and his troglodyte cronies had better believe that the American people would object to that, too.

I’m not even going to respond to the whole God thing Senator Rapert spewed on and on about in his column. The United States of America is not a theocracy, and Senator Rapert and his ilk may not cherry-pick their favorite version of the Bible to oppress people with Iron Age laws. If immigration rates continue the way they have been, pretty soon a majority of Americans will be Papists. Does he want a Catholic nation just because the majority of the population attends mass?

If the basis for a law is Biblical, it should immediately be suspect, and it should bear intense scrutiny. The science and research do not support these laws, no matter what they are.

Arkansas voters and legislators have an unpleasant history of maintaining an unequal status quo. When men make decisions for how a woman may take care of her own body, when straight people make decisions for how gay people may create and care for their families, when white people make decisions about whether black people can take part in the electoral process, there is a very real danger that the dominant and privileged among our population can – and will – oppress those whose voices are not as strong. That’s why the constitutional safeguards of equal protection and due process exist.

Oh, and

P.S. It’s not “activism” for a judge to uphold the constitution.

Obviously, I do not hold much respect for these people. The sign that summed them up for me read,

Obviously, I do not hold much respect for these people. The sign that summed them up for me read,