When my grandmother had me proposed for membership in the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America (NSCDA) in the mid-1990s, I understood that I needed to choose one of my many notorious colonial American ancestors to qualify. My great-grandmother, grandmother, grand-aunts, mother, and mother’s first cousins had all joined through different colonial ancestors. I was already familiar with the well-researched family chart my grandmother had given my mother, which had inspired me to embark on my genealogical quest years before. By my count, I had eighteen colonial-era men listed in the NSCDA’s Register of Ancestors (ROA), and at least another ten of my male colonial ancestors met the Dames qualifications but did not yet appear on the ROA.

To my great and lasting disappointment, however, the direct ancestor I admired the most, whose influence over colonial neighbors and society was significant and reached into the two earliest New England colonies and then beyond, did not appear on the list.

She was a woman.

The NSCDA’s requirements for qualifying ancestors specified that an ancestor had to have given some significant public service to their colony, and the categories were almost exclusively limited to military service, public office holders, founders of significant colonial towns, and religious leaders. They were male, practically without exception, because only males could serve in those formal capacities, and only the signatures of the men appeared on public documents proving such service. The names of women rarely appeared in public records. It especially jarred me to realize that these men who qualified based on founding significant towns such as Providence, Rhode Island, were almost always married, but their wives were never listed as founders.

One of the female exceptions to the NSCDA’s Boys Club was my favorite ancestor’s sister, Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Anne was notorious for being prosecuted and then exiled from Boston in the winter of 1638 for having the audacity to preach to the women of Boston and even (gasp!) challenge the positions of several respected local preachers. She and Mary Dyer, another outspoken preacher, appeared on Massachusetts’s list of accepted ancestors. Anne’s sister and Mary’s friend, Katherine Marbury Scott, who moved to Providence Plantations when Anne was tried for heresy, did not appear in the ROA.

I asked about adding Katherine to the list. I’d happily prove her preaching, notoriety, and challenge to Massachusetts Governor John Endecott. I don’t recall if I only approached the Arkansas Registrar or communicated with the Rhode Island Registrar or genealogist about her. Ultimately, I was told to pick someone else. I was told that unlike Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer, Katherine didn’t famously preach, nor was she arrested, tried, or punished for her religious objections.

But she did, and she was!

To the dismay of Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop – the man who acted as her sister’s accuser, judge, jury, and executioner – Katherine influenced Roger Williams, the famous Anabaptist preacher who was the first colonial advocate for the separation of church and state. At least partly due to her influence, Williams agreed that infant baptism was inappropriate and broke from the Puritans of Massachusetts.1Winthrop, John, The History of New England from 1630-1649, Hosmer, ed., p. 297, available at https://archive.org/details/winthropsjournal00wint.

Katherine and her husband were the first known Quakers in the American colonies and spread the Quaker philosophy and practice among the populace. In her late 40s, she was imprisoned, stripped to the waist in public, suffered ten cruel lashes from a knotted whip, and threatened with hanging if she didn’t keep her mouth shut from here on out. Two of her young daughters – one only 11 years old – went to prison with her. Katherine’s crime was objecting to the mutilation of Quakers. The older imprisoned daughter later married one of the mutilated Quaker men in England.

But somehow, this wouldn’t count? Katherine – and her daughters Patience and Mary – should qualify as NSCDA ancestors because of their overt advocacy of religious freedom.

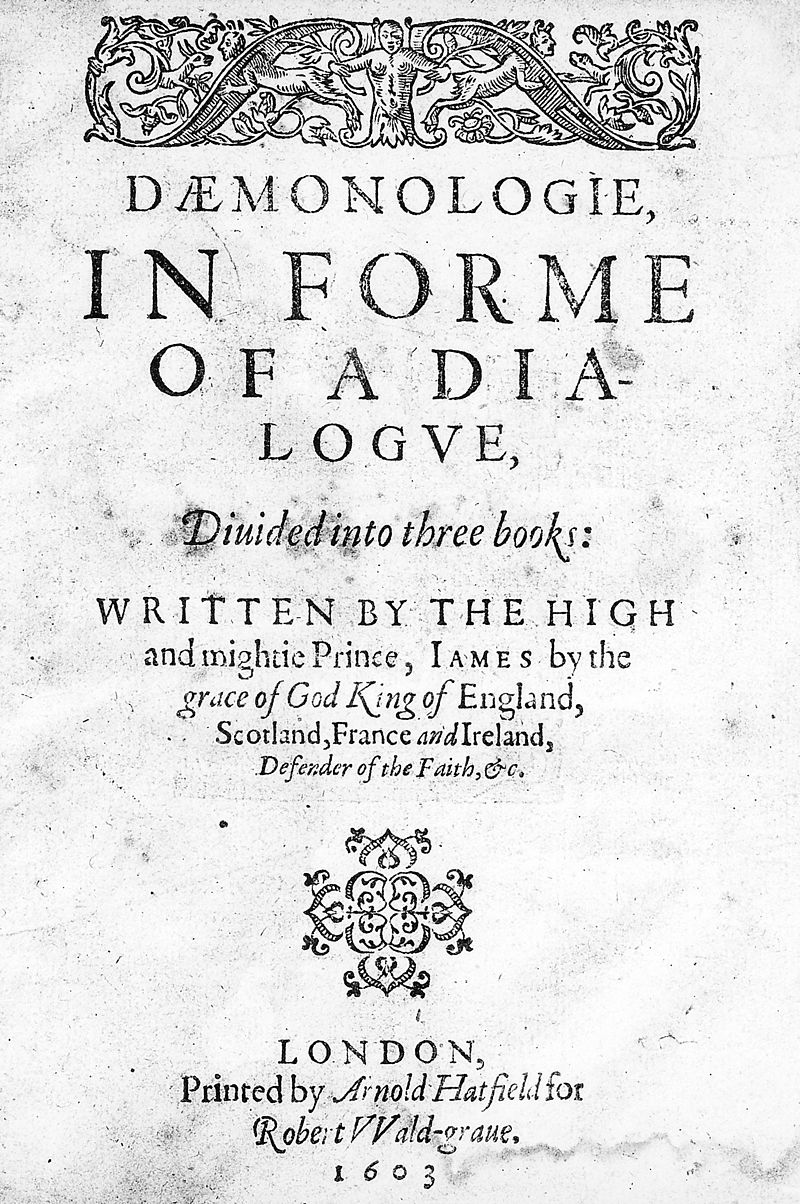

Americans universally claim religious freedom as one of the founding principles of our country. The Protestant Reformation was in full swing when religious separatists boarded the Mayflower in 1620, joined the Winthrop fleet in 1630, fled to William Penn’s Quaker utopia in the 1690s, and embraced the Great Awakening in the 1730s.

In fits and starts, and despite theocratic local governments in the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies and parish control of government functions in Virginia and Carolina, notions of religious freedom spread and permeated all of colonial America. George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights declared that reason and conviction should direct a person’s religion, not force or violence. The first item in the Bill of Rights appended to the United States Constitution includes the free exercise of religion and the freedom from government interference in religion. In 1789, France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man – heavily influenced by American ideals – maintained that “No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views.”

On top of all of this, the NSCDA limited its membership to women but excluded nearly every colonial woman from their list of qualifying ancestors. Why? Did its governing leaders honestly think their entire gender had so little to offer in the colonial era? Did they not understand that no colony could succeed without women? The founders of Jamestown certainly came to understand that in short order. Even so, the NSCDA’s Register of Ancestors included very few of Jamestown’s early women. Those it did include had to be wealthy, powerful, and independent – something legally impossible under coverture laws except in extremely limited circumstances.

I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a part of this group.

In passive-aggressive protest, I let my application linger for several years. Genealogy was my hobby and passion, and I could have chosen any of the ancestors my relatives had already proven. The injustice of not accepting Katherine rankled me.

My grandmother insisted I join, and my mother badgered me to complete my application. Neither could understand why I didn’t pick someone already on the list and get the paperwork done. After all, genealogical research was my passion, and I could copy any of the applications of my many Dames relatives in short order. It wasn’t that big a deal, was it?

Yes, damn it, it was.

Bowing to their pressure, I finally decided to join based on Katherine’s husband’s recognized service. He was wealthy and influential but didn’t impress me nearly as much as she did. He seemed a solid, principled man, sure. Still, he only embodied the usual among my colonial ancestors: he was an educated landowner who bravely went to a new place to start a new life and took part in the political affairs of his community. Beyond that, he did not spark my imagination.

Two or three years ago, the NSCDA had a change of heart. At a national level, it decided to push to include more women in the Register of Ancestors. It set a goal of having 250 females included on the ROA by the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The individual colonial states set the guidelines for ancestor qualifications, though, and other than Virginia, the colonial societies seemed reluctant to widen the qualifying “service” women might have legally been able to give. Foot-dragging stymied this otherwise attainable goal.

Rhode Island, where Katherine Marbury Scott lived, finally expanded their qualifications in 2024. (I’ve been watching for it.) Other colonial states are just as slow, if not slower. For example, Eliza Lucas Pinckney still doesn’t appear on South Carolina’s list of acceptable women despite her herculean accomplishments in cultivating indigo and refining the process of extracting its dye. Because of her singular efforts, indigo became one of her colony’s three staple exports in the 18th century. Massachusetts finally expanded its list of qualifications so applicants for membership could claim Women of Distinction. The first colonial American poet, Anne Bradstreet, finally counts.

The blatant misogyny and snobbery of the organization still flabbergasts me. Are the NSCDA’s colonial societies afraid that if they expand the qualifications to include women, men who did the same important things – men of science and letters, for example – might suddenly qualify, and the “wrong sorts” will pollute the Register of Ancestors?

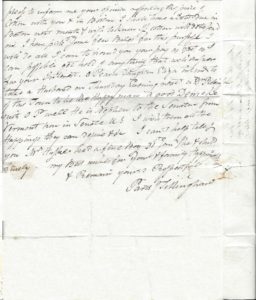

I have a few men of science and letters in my tree who I’d like to include, like Dr. Benjamin West of Providence, Rhode Island, a prominent man of both science and letters who never held public office, never preached, never served as an officer in the military, and wasn’t wealthy enough to join the board of organizers of what is now Brown University.

I want to claim John Perkins, who, as a youth, led the important Moravian expedition that ultimately resulted in the founding of Salem, North Carolina. He was the son of a horse thief and a notorious adulteress but became prosperous, prominent, and one of the largest landowners in 18th Century Western Carolina. Without a doubt, he represents the wrong sort for the Colonial Dames. Never mind that the murderer John Billington qualifies because he came on the Mayflower or that his fellow Mayflower passengers Edward Doty, Stephen Hopkins, William Latham, and Richard More also built impressive rap sheets in colonial America.

The Dames’ snob factor is real. Several larger southern state societies of the NSCDA actively refuse admission to genealogically qualified women, including the legacies of their current members. While such selectivity and elitism may appeal to some, it’s appalling to others. The NSCDA is a lineage society, not an exclusive country club.

Am I complicit in this snobbery and misogyny? I have been a member of the NSCDA for over two decades. I have served on the Arkansas Society’s board since 2005 and have been its Registrar or Assistant Registrar since 2013. As Registrar, I process the applications of candidates for membership. I do most of the genealogy research for our candidates myself. I am intimately familiar with the policies for qualifying ancestors. I am also intimately familiar with the snobbery.

At a Regional meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, I sat at a table with a member from Memphis. The evening’s entertainment was an actor portraying Thomas Jefferson. A notorious DNA project had recently confirmed Thomas Jefferson to be the father of Sally Hemings’s enslaved children. I remarked to my dinner companion that because of DNA technology, it would be much easier for Black women to join the NSCDA. To my knowledge, there were no Black Dames at that time.

She gave me a look of abject horror. Apparently realizing that she shouldn’t be racist, she said that such people couldn’t join because they couldn’t prove legitimate descent from the qualifying ancestor. I laughed and told her that DNA proves actual descent, and the NSCDA has never required legitimacy. Her reaction to that news made me think she was about to have a fit of apoplexy.

For years, in the password-protected section of the NSCDA website, a letter from a prominent early Dame, Clarinda Pendleton Lamar, was posted as an example of who to invite to join the Dames. Clarinda Lamar cautioned proposers to consider whether the candidate for the NSCDA was a credit to her race, her ancestors, and her community. During my first term as Arkansas Registrar, the NSCDA’s national president visited us and was present for a board meeting. At the time, two existing members had to write proposal letters to suggest a candidate for Dames membership. They had to know the candidate well and vouch for her. Our bylaws required us to read the proposal letters aloud during two separate board meetings, after which the board would vote on whether to invite the proposed candidate to apply for membership in the NSCDA. To the best of my knowledge, Arkansas has never rejected a proposal.

When we got to the proposal-reading portion of the agenda, the national president suggested reading Clarinda Lamar’s letter aloud to remind us what qualities we should look for in a candidate. After reading the “credit to her race” line, I stopped. “Well, that’s awful,” I said. Nervous laughter went around the table.

I advocated removing the Lamar letter from the website at subsequent national conferences in Washington, D.C. While most of Clarinda Lamar’s contributions to society were significant and good, that letter represented the worst of what we can be. It was patently unsuitable as the lodestar of membership. At one meeting of all the Registrars nationally, around 2016 or 2018, I repeated my request to remove it. On receiving pushback, I lifted my middle finger prominently skyward. I declared that Clarinda Lamar’s racism did not speak for me or the Arkansas Society and that having the letter there was an embarrassment. She was a product of her time, yes, but just like we stopped ignoring when people in positions of power demanded sex from their subordinates – and I specifically mentioned Thomas Jefferson and casting couches – we needed to stop ignoring racism because by ignoring it, we promoted it.

There was a general outcry, but after the meeting, several Registrars approached me privately and thanked me for pointing that out. A couple of others later admitted they had never read the letter until my words prompted them to do so, and they agreed that it should be taken down. In 2024, the National Society overhauled the website. The Lamar letter no longer enjoys publication there. Nevertheless, my beloved friend and successor Arkansas Registrar has never let me live down “the day [I] flipped off Mrs. Lamar” in front of 50 devoted Colonial Dames.

In October 2016, at another National meeting in Washington DC, I found myself seated between my counterpart in Vermont, who I liked very much and remain in contact with, and a woman from Arizona. Barack Obama was about to leave the Oval Office, and Donald Trump, the primary denier of Obama’s American citizenship, wanted his job. This Arizona woman bragging about her close personal friends the Koch brothers, stuck in my craw. I turned to my Vermont friend and suggested we ask the DC Dames if they’d reach out to the Obama sisters to ask if they’d like to join our lineage society. After all, they qualified through their father’s ancestors. I would be happy to do the genealogy research, and getting our hands on their father’s birth certificate, which would be necessary to prove their colonial lineage, was a matter of public consumption at this point. The Obama girls also had a half-Indonesian aunt who qualified because of the same lineage. We would finally integrate the Dames!

We did approach the DC Dames’ Registrar about it, but nothing ever happened. I remain ready, willing, and able to compile the applications for the Obama sisters and their paternal aunt.

I have taken other steps to make changes from within this organization. I have completed applications for NSCDA membership for women whose home societies would not let them join, and then I’ve processed transfers to their home societies. The National Society requires that transfers be automatically approved. Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas have all benefitted from my end-run around their blackballing town committees. I will do it again whenever I can. I can’t abide the snobbery.

Change comes from within. I can do more to challenge the Colonial Dames’ culture of elitism and snobbery as a member than I can by refusing to participate and letting it go on. I can advocate for change, I can take steps to rectify wrongs, and I can, incrementally, make it better. I do not support racism or snobbery any more than Katherine Marbury Scott supported religious oppression.

Footnotes

- 1Winthrop, John, The History of New England from 1630-1649, Hosmer, ed., p. 297, available at https://archive.org/details/winthropsjournal00wint.