I can thank my migraines for Dr. Benjamin West.

When I am anxious or don’t feel well, I often do genealogy research to take my mind off things. I have always enjoyed learning about family history, but really got bitten hard by the bug the first time I had cancer, in 1994. I was at home recuperating, on painkillers and other drugs that made concentrating difficult, and I found message boards on AOL that were all about genealogy. And my ancestors were there! I connected with some very distant cousins and compared notes. I started learning more and more about my origins.

It occurs to me that we are all the products of our parents, who are the products of their parents, who were the products of theirs, and so on. Our parents don’t just pass genetics on to us. Even when we disagree about things like politics or religion or how to raise our children, the values of our parents are distilled into us, just like the values of their parents were distilled into them. We find that professions tend to run in families – a certain branch of the family may tend to be lawyers, writers, preachers, doctors, architects, artists, military, etc.

An obituary notice in a newspaper from 1822 led me to him. He was named as the father of one of my 5th great-grandmothers, a woman whose origins were completely unknown to me before that moment. The man was phenomenal, and I don’t understand why every generation after him hasn’t continued to hold him up as the pinnacle of the Enlightenment. This guy’s brain was so huge and active I don’t know how it managed to stay confined in his skull.

Benjamin West was born in Bristol, Massachusetts in March 1730. I think of him as the Stephen Hawking of his day. His accomplishments in math and science are truly remarkable because he was an autodidact – his formal schooling lasted a whopping three months of his childhood. He was poor and had to borrow every book he read until about 1758, when he managed to find some backers to open a dry goods store. A couple of years later, he opened the first bookstore ever to grace the commercial avenues of Providence, Rhode Island. He managed to pay for the books he so desperately wanted by selling them to other people.

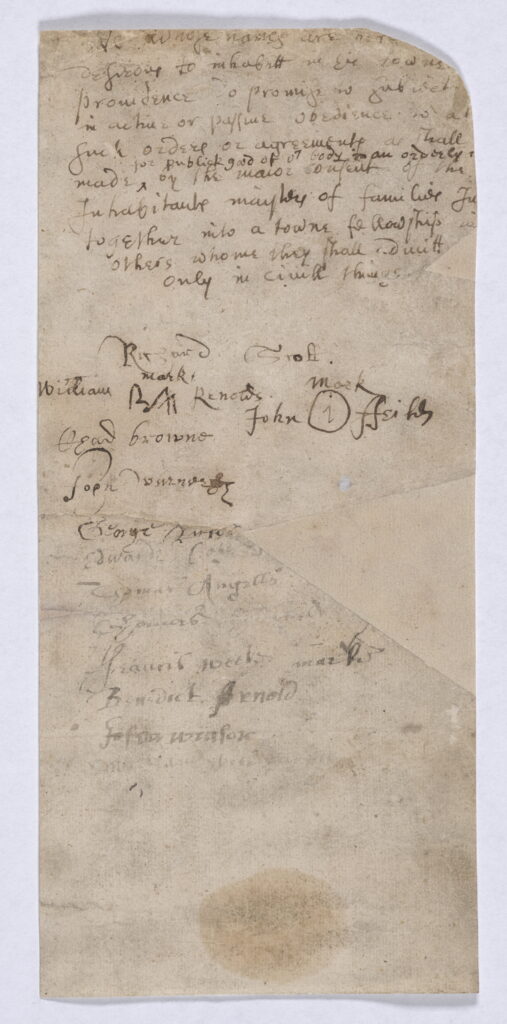

He married Elizabeth Smith, daughter of Benjamin Smith, in 1753 when he was 23. They were married for 53 years and had eight children, only three of whom survived Benjamin. The 1822 death notice for his daughter, Mary Smith West (wife of Oliver Pearce), in a Providence newspaper, alerted me to him. The death notice that mentioned her father was “Dr. Benjamin West of Providence.” Mary West Pearce died in Fayetteville, NC. Her daughter, Eliza West Pearce, married Dr. Benjamin Robinson, that guy from Vermont who tested out that newfangled smallpox vaccine on his little brother and his brother’s friends and basically got run out of Bennington for his efforts. Science is strong in my family!

Benjamin West was a brilliant mathematician and astronomer. His buddies were the founders of Rhode Island College, which later became Brown University. He loved mathematics and astronomy, and conferred with some truly fantastic minds of his day. He published annual almanacs for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Providence, Rhode Island for nearly 40 years. He didn’t have the formal schooling necessary for good academic chops, though, and before he opened that dry goods and book store, he failed at operating a school. He tutored students privately for all of his adult life.

Astronomical Genius

In 1766, something would happen that ultimately would reverse his fortunes and open some gilded doors for him. A comet appeared in the constellation of Taurus on the evening of April 9. Being a good astronomer, Benjamin took careful measurements. The next day wrote a letter to an astronomer named John Winthrop who was at Cambridge College (now known as Harvard University). He had never met or corresponded with Winthrop, but was so excited about his observation he simply had to share it.

Providence, April 10, 1766

Dear Sir:

For the improvement of science, I now acquaint you, that the last evening, I saw in the West, a comet, which I judged to be about the middle of the sign of Taurus; with about 7 degrees North latitude. It set half after 8 o’clock by my watch, and its amplitude was about 29 or 30 degrees. Nothing, Sir, could have induced me to this freedom of writing to you, but the love I have for the sciences; and I flatter myself that you will, on that account, the more readily overlook it.

I am, Sir, yours,

Benjamin West

He and Winthrop became great friends and continued to write to each other. For the rest of their lives, they would share observations about the night sky.

1769 Transit of the Planets

Johannes Kepler and Edmund Halley figured out how to apply the theory of parallax to determine the distances between astronomical bodies. With both Mercury and Venus predicted to pass between the Earth and the Sun in 1769, astronomers worldwide were anxious to test the theory. Since this was the first really good opportunity to view the transits of both inner planets since Kepler’s original accurate prediction in 1627 of the 1631 transit, everyone in the field of astronomy was excited. Captain Cook would famously observe the 1769 transit of Venus from Tahiti while on his ill-fated circumnavigation and while bringing European diseases and disharmony to the South Pacific. At the time of the last transit of Venus in 1761, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, who had just finished their survey of the boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland, had traveled to the Cape of Good Hope to observe it. All of these men used astronomy as an important part of their lives – navigating the oceans and surveying the land required precise measurements, and measurements started with the stars.

There was no telescope in Providence in 1769. Benjamin West, Stephen Hopkins (the signer of the Declaration and great-grandson of the Mayflower passenger) and the four famous Brown brothers – they were among the founders of Rhode Island College, later known as Brown University – were determined to see the phenomenon, though, so they managed to import a telescope from England at the incredible expense of 500 pounds. They set up on the outskirts of Providence. Transit Street in Providence is named after the spot where they viewed the transit on June 3, 1769. There are photos of the telescope on the Brown University website – the school still has it.

As was his habit, Benjamin West made careful measurements of the transit. He published a tract (and dedicated it to his friend Stephen Hopkins) about the event. A copy of the tract made its way to John Winthrop at Harvard, and on July 18, 1770, Benjamin West – the man with only three months of formal education – was awarded an honorary Master of Arts from Harvard. Here’s the text of the notification letter from John Winthrop:

Cambridge, July 19, 1770

Sir —

I have the pleasure to acquaint you that the government of this college were pleased, yesterday, to confer upon you the Honorary degree of Master of Arts; upon which I sincerely congratulate you. I acknowledge the receipt of your favour, and shall be glad to compare any observations of the satellites.

Yours,

John Winthrop

American Academy of Arts and Sciences: the American Philosophical Society

That same year, Benjamin West was unanimously elected to membership in the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia – the American colonial version of Great Britain’s Royal Society. He would meet and befriend another author and publisher of almanacs there: a fellow named Benjamin Franklin.

Benjamin West was still primarily a merchant at this time, and the Revolution was on its way. When full-blown war finally arrived, commerce dried up. He went to work manufacturing clothing for the American troops. He continued his studies and his correspondence with the other great minds, though.

Mathematics was Benjamin’s first love. In 1773 he wrote to a friend in Boston of a theorem he had developed to extract “the roots of odd powers” that was probably his greatest contribution to the field of mathematics. That’s right – he discovered a math formula that I can’t even begin to hope to understand, but other really smart people who could math really well understood it and lauded him for it. When he finally explained his theorem to other math geniuses in 1781, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences not only published it in one of their earliest journals but unanimously elected him to membership and awarded him a diploma. It was his second honorary academic degree, and he still supported by only three months of formal education. The theorem caught the attention of the European mathematical geniuses, who, giddy with discovery, also published it. Benjamin West, already pretty cool, became seriously hot stuff.

He didn’t stop at math and astronomical observations, though. One of the biographies I found explained a physics problem he cogitated upon for more than two years in conjunction with John Winthrop and a Mr. Oliver. It had to do with the properties of air in a copper tube that was then put into an otherwise airless container. The qualities of invisible gases – basically, the scientific understanding of the very concept of the physical nature and properties of “air” – were in their infancy. Our ancestor speculated about the attractive and repulsive nature of the tiny particles that made up the matter of air – what we now call its molecules – and how they would behave under different conditions. Gravity, matter, magnetism, and ultimately the behavior of the tails of comets played into his understanding of the question. This is stuff my brain simply isn’t big enough to handle.

Benjamin West’s mind was at the peak of its illuminating brilliance as the world around him heaved. His most important discoveries and writings happened as the American Revolution was about to explode. By the end of the Revolution, he had returned to academic pursuits. He tutored students in math and astronomy. He still wasn’t rich; despite his prominence in academics he never became particularly wealthy. The well-endowed founders of what would become Brown University had not forgotten their friend, though. In 1786, he was elected to a full professorship there.

For some reason, he did not begin teaching at Brown for a couple of years. Probably because of his honors and his friendship with Ben Franklin and the rest of the gang at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Benjamin West was invited to teach at the illustrious Protestant Episcopal Academy there. The name of that school is familiar to members of my father’s family. Although Benjamin West was the direct ancestor of my Arkansas-born mother, my dad, an Irish-Italian kid who grew up in the Philly suburb of Gladwyne, went to school at Philadelphia’s Episcopal Academy while his dad coached its sports teams. (Insert refrain from “Circle of Life” here.)

Brown University awarded Dr. West his first non-honorary degree, his Doctor of Laws, in 1792. He taught mathematics and astronomy there from 1788 until 1799. Then he opened a school of navigation and taught astronomy to seafaring men. Like Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson, this man loved to teach other people the wonders of the universe.

I’m proud of him for another reason, too: Benjamin West was a member of an active abolitionist group in Providence.

I’ve found several contemporary biographical accounts for Benjamin West. They are typical of their time: purple prose and flowery metaphors abound. They all reach one conclusion: Benjamin West was a genius. He was a determinedly self-educated man who contributed considerably to the arts of science and mathematics during his lifetime. He was truly a product of the Age of Enlightenment: a self-educated, self-made man whose gifts and prominence considerably exceeded his bank account.

This discovery of my ancestor Benjamin West is exactly why genealogy research is so rewarding. And given the anxiety-provoking events of November 8, I expect to be doing a lot more of it – in between my stepped-up schedule of political activities, that is.

Bibliography:

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Book of Members (2016 edition), p. 252. Entry for Benjamin West, elected 1781, Fellow. Residence and Affiliation at election: Providence, RI. Career description: Astronomer, Educator, Businessperson, Book of Members; American Academy of Arts & Sciences, American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Leonard Bliss, The History of Rehoboth, Bristol County, Massachusetts: Comprising a History of the Present Towns of Rehoboth, Seekonk, and Pawtucket, From Their Settlement to the Present Time (Boston: Otis, Broaders, and Company, 1836). Google Books

Louise Hall, “Family Records: Newby Bible”, New England Historical and Genealogical Register 122 (Apr 1968): 125-128, 125.

Martha Mitchell, “Benjamin West”, Encyclopedia Brunoniana (1993).

John Chauncey Pease, John Milton Niles, A Gazetteer of the States of Connecticut and Rhode-Island: (Hartford: William S. Marsh, 1819), 331-333. Biographical entry for Dr. Benjamin West. Google Books.

Unattributed, “Biography of Benjamin West, L.L.D. A.A.S.: Professor of Mathematicks, Astronomy and Natural Philosophy, in Rhode Island College – and Fellow of the Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, &c.”, The Rhode Island Literary Repository Vol I, No. 7 (October 1814): 137-160 (337-360).

Benjamin West Papers; Rhode Island Historical Society Library, 121 Hope Street, Providence, RI 02906.